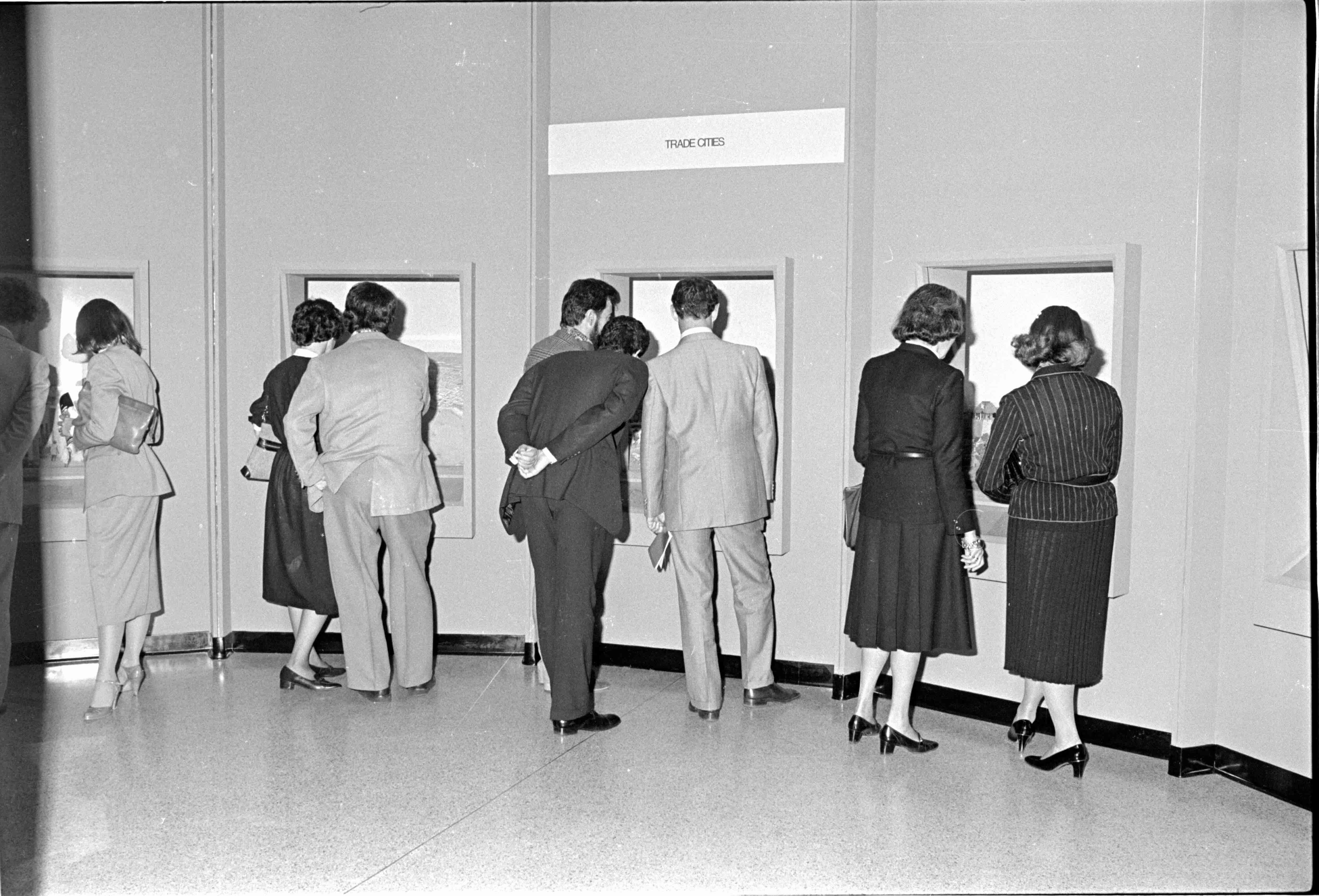

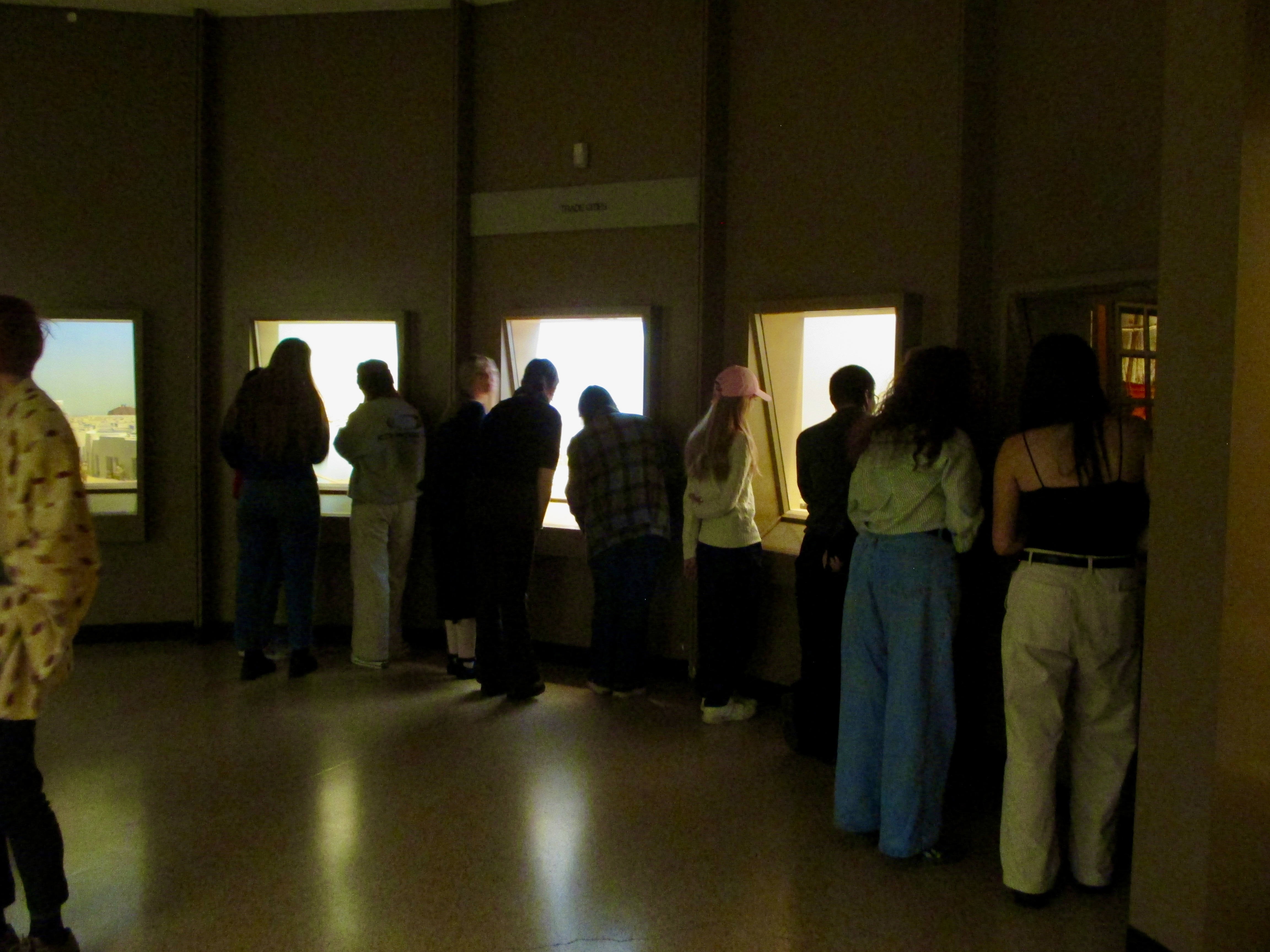

Asian Friends Reception, opening of the Gardner D. Stout Hall of Asian Peoples, 1980. [photo credit] AMNH Research Library, PPC.445 G37

Miniature dioramas have long been used in museums to depict cities, scenes, and figures with astonishing detail. At the American Museum of Natural History, they have played a crucial role as educational tools, offering visitors a glimpse into different times and places through these small-scale worlds. However, miniature dioramas often simplify the complexity of each city’s rich history and the connections between them. Further, they contain many errors and reflect common stereotypes.

This digital companion recontextualizes and reexamines the role of miniature dioramas in museums by focusing on three trade city dioramas—Isfahan, Beijing, and Kolkata—in the American Museum of Natural History’s Hall of Asian Peoples. Through this exploration, we invite viewers to reflect on what these dioramas truly represent and their limitations as portrayals of historical pasts.

Behind the Construction

Creating miniatures is no small feat! Each trade city diorama, on average, took about two years to fabricate and install. Between 1973 and 1977, George Campbell, a Museum artist, designed and worked on the 3D elements of each trade city highlighted here. As a naval architect and model ship maker, he had the patience and skillful hands to bring the project to life. Alongside Campbell, Robert Kane created the background paintings. He was also the artist behind many stunning murals across exhibits in the Museum that blur the line between painting and three-dimensional arrangement.

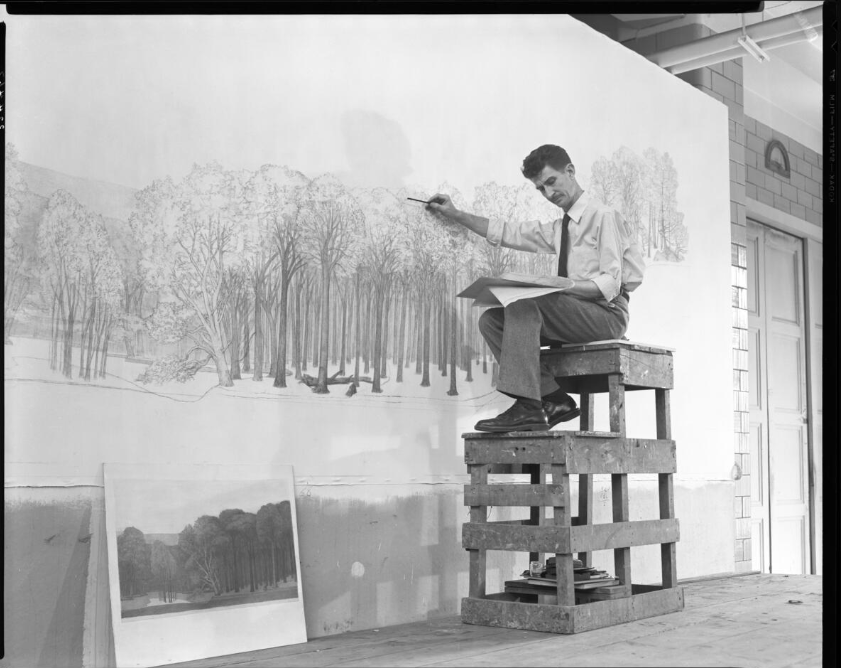

George Campbell looking at the model of the ancient city of Isfahan in Iran which he created, Gardner D. Stout Hall of Asian Peoples 1979

[photo credit] AMNH Research Library, PSC81I

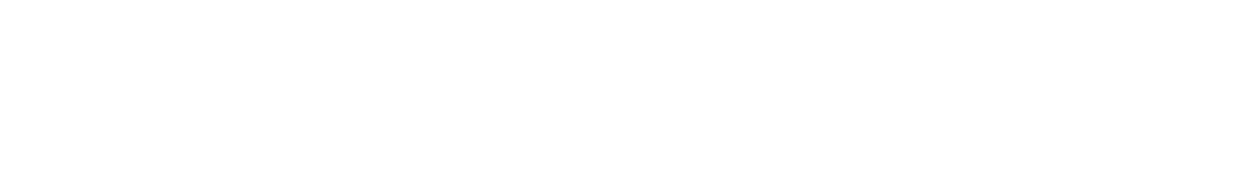

Robert Kane laying out mural for Hall of American Forests, 1956.

[photo credit] AMNH Research Library

What’s Wrong with Miniature Dioramas?

While miniature dioramas in museums are charming, they can also be problematic. They were created by drawing from various sources, such as paintings, photographs, oral histories, and travel guides. These sources were used to help designers and curators represent the cities, influencing how they are perceived and understood. However, the origins of these sources are not always rooted in the culture that they mean to depict, and in some cases, materials from one time period are used to represent another. This creates a densely layered, and sometimes misleading narrative. In this process of miniaturizing, cities are pulled from time and space and become consumable spectacles behind glass.

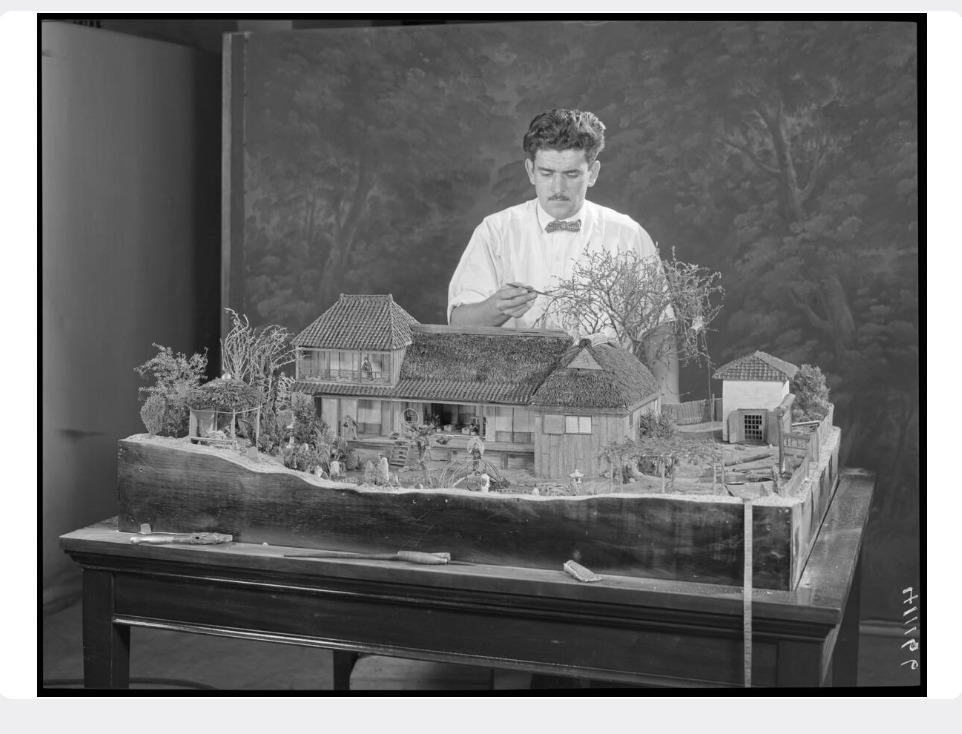

Vernon R. Short working on a miniature of a Japanese country home, 1929.

[photo credit] Dutcher, Irving (photographer). AMNH Research Library

Under the Glass

Take a closer look at these miniature dioramas and learn more about how they shape our understanding of the cities they represent with this interactive game!

Under the Glass

Take a closer look at these miniature dioramas and learn more about how they shape our understanding of the cities they represent with this interactive game!

ISFAHAN

SAFAVID DYNASTY

1501–1736

Isfahan, the capital of the Safavid Dynasty, was a cultural hub known for its influential Iranian architecture and booming trade economy. Yet this miniature diorama actually represents post-Safavid times as well as blurring its rich history with Western fantasy.

BEIJING

MING DYNASTY

LATE 1400s

Emperor Yongle (1403–1424) expanded China’s land and sea trade, which peaked from 1405–1433, when Zheng He’s voyages linked Asia and Africa. Beijing emerged as a central hub for goods exchange, tribute payment, and cultural interaction between the East and the West.

About the Project

This project was done as part of the 2024-2025 Museum Anthropology Masters’ program jointly offered by Columbia University and the American Museum of Natural History. However, this project could not have existed without the help of many others at the University, the Museum, and Beyond.

Thanks to:

MUSA 2024-2025

Curating, Writing, Exhibit Design (by groups)

Project Leaders

Siyang Dai & Sydney DeBerry

Miniatures

Iris Bennett

Siyang Dai

Celene Lignell

Isfahan

Sydney DeBerry

Margot Hahn

Hailey Paetzel

Adele Roulston

Beijing

An Hoang

Siyang Dai

Yanming Bi

Kolkata

Sydney DeBerry

Akrivi Liosi

Kaila McKiernan

Professors

Laurel Kendall, Division of Anthropology and Curator, Asian Ethnographic Collections, AMNH. Adjunct Professor, Columbia University

Ciné Ostrow, Senior Exhibit Designer, AMNH

Editor

Allison Hollinger, Exhibition Researcher/Writer

Exhibit Graphic Design

Jennifer Dillon

Web Designer

An-Kai Cheng

AMNH Division of Anthropology

Barry Landua, Systems Manager and Manager of Digital Imaging

Kristen Mable, Anthropology Archivist

Bindy Kaye, Anthropology Archives volunteer

Katherine Skaggs, Senior Museum Specialist, Asian Ethnology

AMNH Library

Rebecca Morgan, Special Collections Archivist

Gregory Raml, Special Collections Librarian

Mai Reitmeyer, Senior Services Librarian

Special thanks to

Brian Boyd, Director, Museum Anthropology M.A. Program Senior Lecturer in the Discipline of Anthropology Co-Director, Center for Palestine Studies at Columbia University Co-Chair, Columbia University Seminar on Human-Animal Studies

Susan Bean, Senior Curator of South Asian and Korean Art, Peabody Essex Museum (retired)

Farshid Emami, Assistant Professor of Art History, Rice University

Rachel McDermott, Professor of Asian and Middle Eastern Cultures, Barnard College, Columbia University

Morris Rossabi, Associate Adjunct Professor, Columbia University

This project was made possible with the generous support from both the Columbia University Department of Anthropology and the Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy, as well as in-kind support by the American Museum of Natural History.