Cosmic Center | Ming Beijing 北京 in the late 1400s

Welcome to Beijing

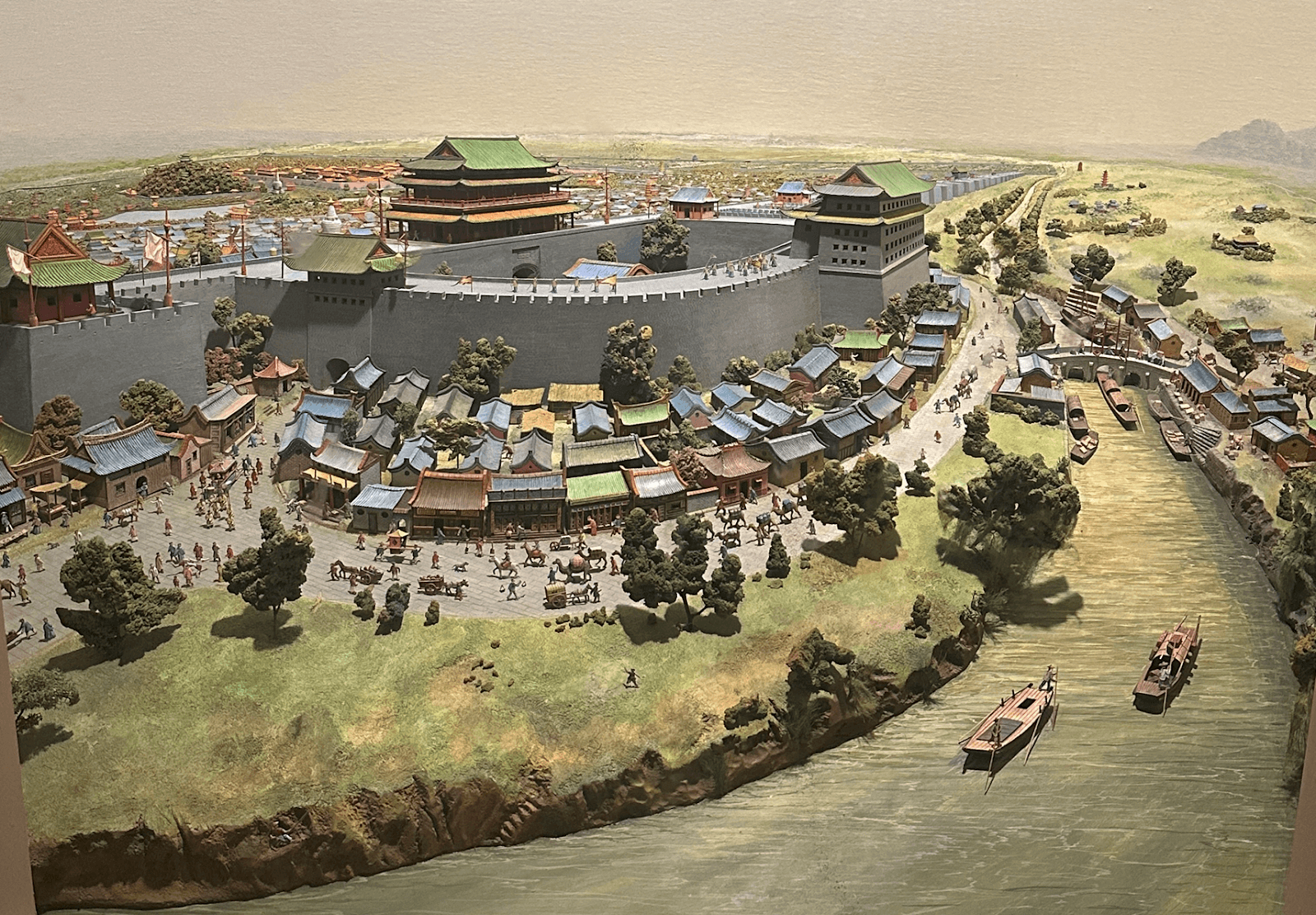

This miniature diorama is meant to show the Ming Beijing city, the “Northern Capital” in the late 1400s, with a particular focus on its vibrant trade scene. In the early Ming Dynasty, under the Yongle Emperor (r. 1403–1424), China expanded the land and sea routes of the Silk Road to its peak. Marked by Zheng He’s maritime voyages to the Indian Ocean, China developed an impressive overseas trade linking Asia and Africa. The capital, Beijing, emerged as a central hub for goods exchange, tribute payment, and cultural interaction between the East and the West.

How to Play:

1. Find Hidden Objects – Look at the photo of the miniature model. Using the Object List for reference, locate the objects with your cursor.

2. Hover for Info – Hover over an object to see an enlarged image and a short description.

3. Learn More – Some objects link to themed sections on the city. Click “Learn more!” to scroll down for more details.

4. Use the REVEAL Button – Stuck? Click REVEAL to turn the invisible rings red and access the pop-ups directly.

How to Play:

1. Find Hidden Objects – Look at the photo of the miniature model. Using the Object List for reference, locate the objects.

2. Click for Info – Click an object to see an enlarged image and a short description.

3. Learn More – Some objects link to themed sections on the city. Click “Learn more!” to scroll down for more details.

4. Use the REVEAL Button – Stuck? Click REVEAL to turn the invisible rings red and access the pop-ups directly.

Object List

Monk

Stupa

Camels

Official’s Clothes

Dog

Forbidden City

Wall & fortress

Wedding Party & Jugglers

Monk in Red Robe

The figure wearing a red robe might be a Tibetan monk, as red is considered a sacred color in Tibetan

culture. From the 1200s to the 1900s, the Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties invited Tibetan monks to Beijing to

serve in court and reside at royal monasteries.

Laufer during the Jacob H. Schiff Chinese Expedition, 1901–1904[Photo credit] AMNH Research Library

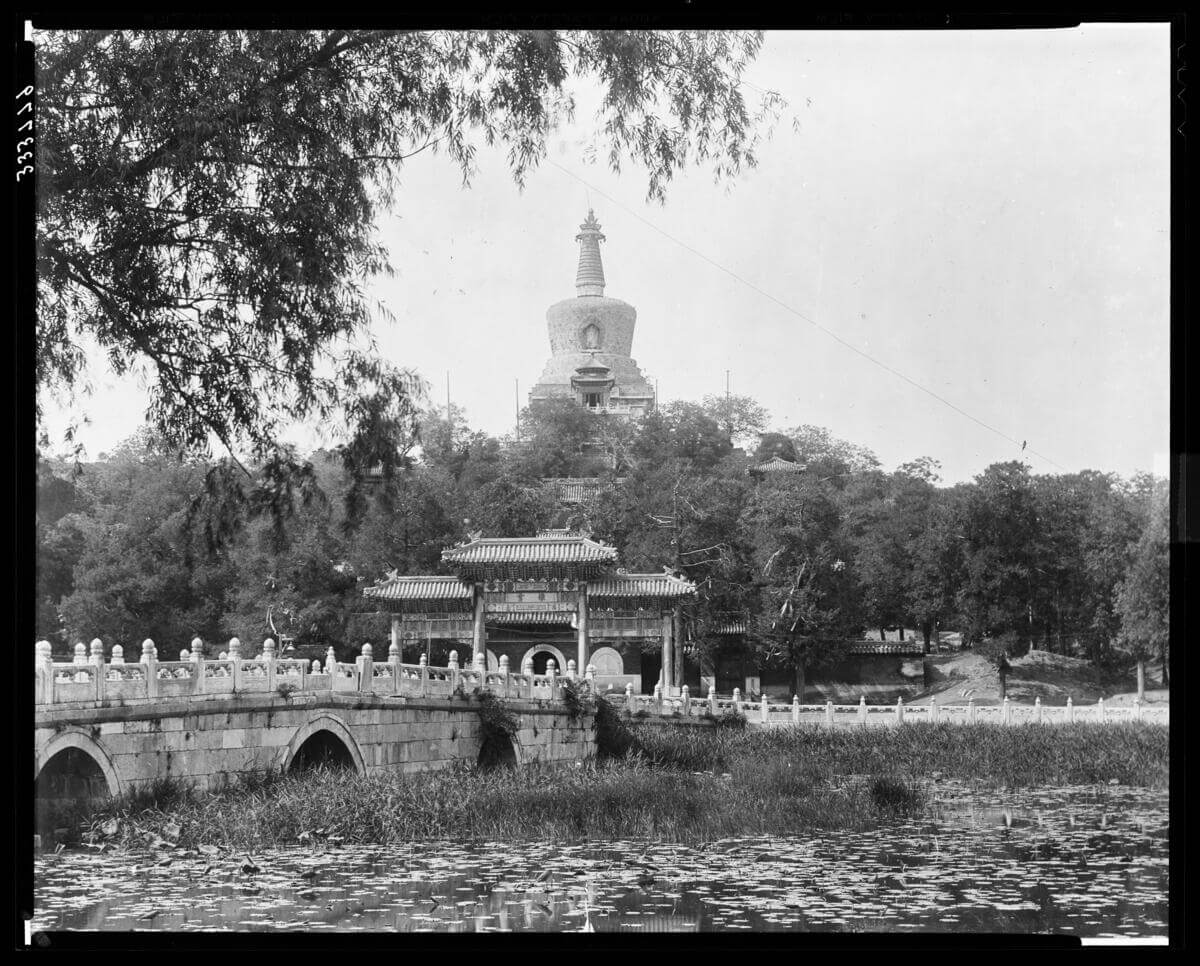

Tibetan Stupa

Stupas are sacred funerary mounds that house relics of the Buddha or revered monks and nuns. There are

Tibetan stupas built in Beijing, dating back to the Mongol-ruled Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). Ming and Qing

emperors (1368–1911) continued to embrace and patronize Tibetan Buddhism well into the twentieth century.

during the Jacob H. Schiff Chinese Expedition, 1901-1904[Photo credit]AMNH Research Library

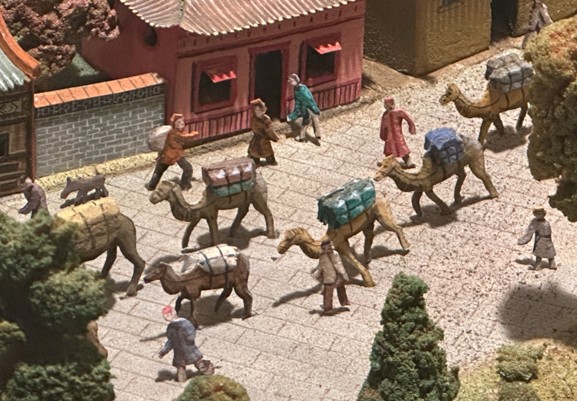

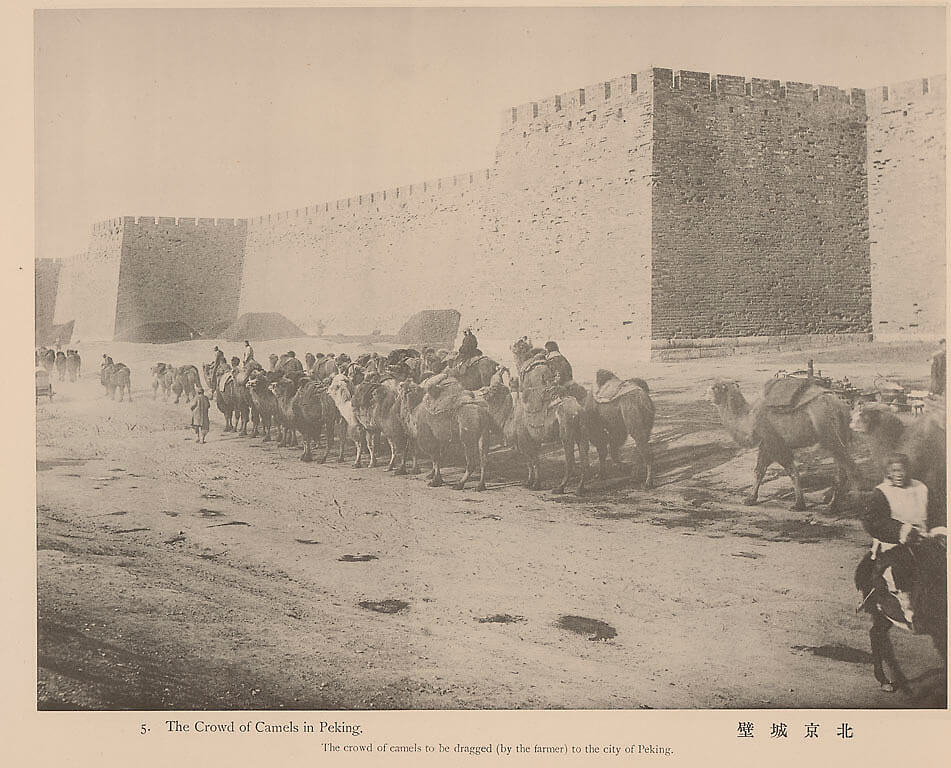

Camels

Camels in caravans were the lifeblood of the ancient overland Silk Road. They carried a variety of goods and

products for exchange, like spices, gems, and textiles. China stood at the center of commercial and cultural

exchanges in the fifteenth century. The Ming Imperial Court demanded the finest goods as tribute, often

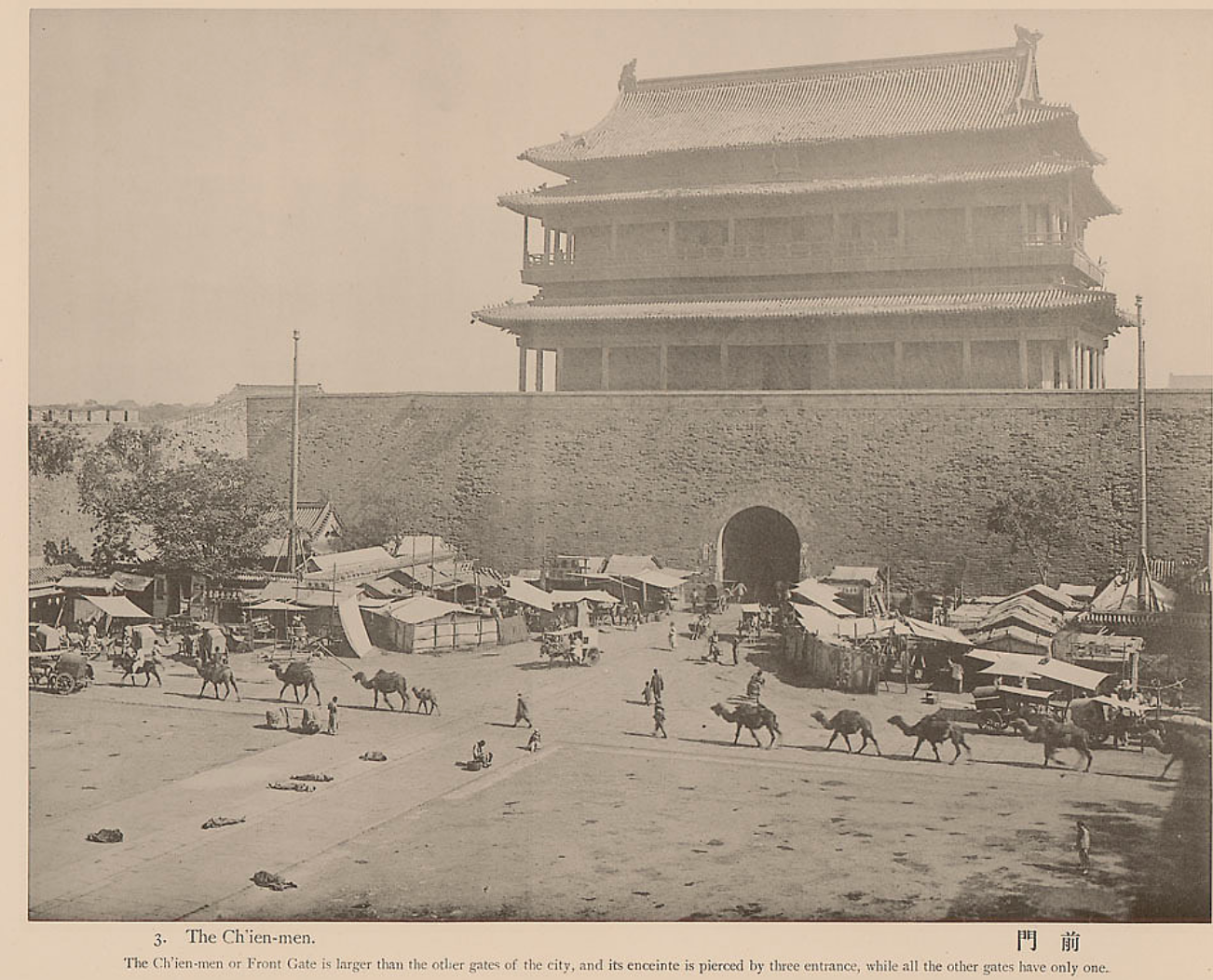

transported to the capital city Beijing on camels, as this photograph illustrates.

or before[photo credit] National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution [NAA INV.04494600].

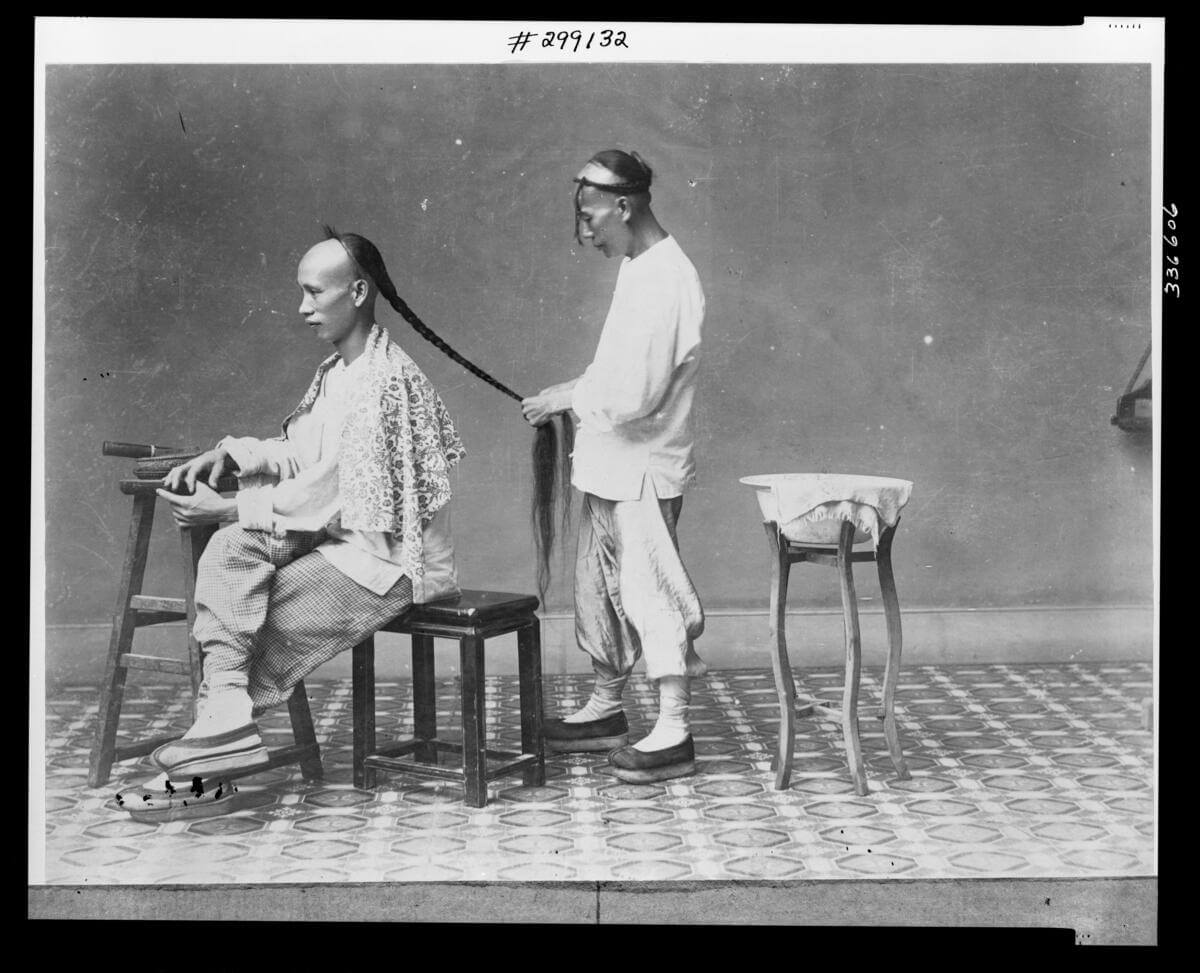

Qing dynasty fashion and hairstyle

This miniature diorama mistakenly depicts Qing dynasty (1644–1911) people, not Ming. Officials wear Qingdai guanmao (Qing official headwear) and clothes cut to accommodate horse-riding and archery, as distinctive of Manchu culture. The Qing imposed the queue on their Chinese male subjects, a single long braid and shaved scalp.

Dog

Do you see the dog in the shadow under the tree? What is the dog doing? This is a hidden gem that reveals a playful side of the artist that made this miniature diorama. What other secrets can you find?

REVEAL

Learn More

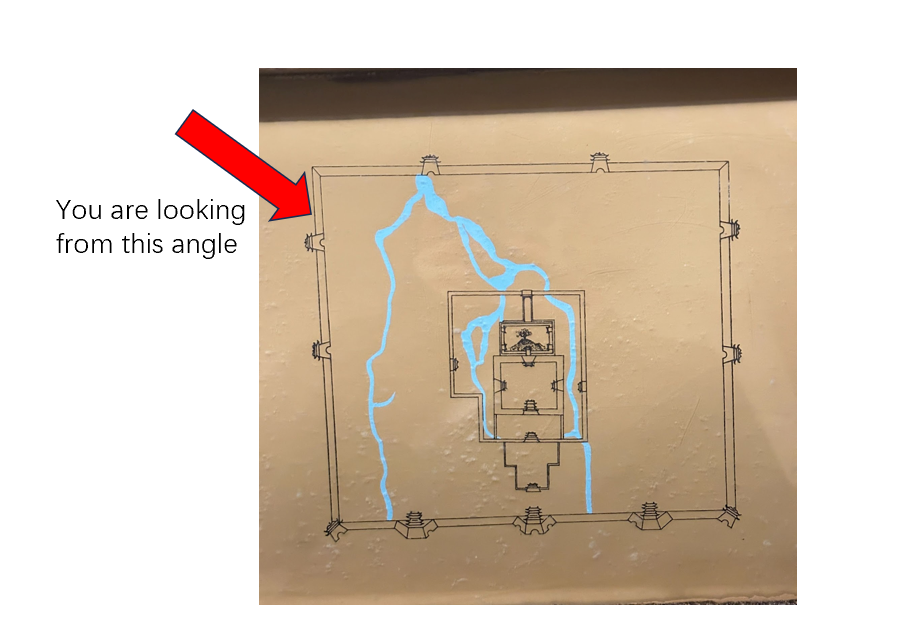

Why does the Angle Matter?

When you look at this miniature diorama of Beijing through the glass, your vantage point is from the northwest corner of the city. In the distance, you can see the Forbidden City, the restricted Imperial residence, enclosed by red walls (mistakenly colored pink in the miniature diorama). However, many important landmarks are misplaced. Moreover, those who conceptualized the layout of a Chinese imperial city intended for it to be seen from south to north, the orientation of most maps of Beijing.

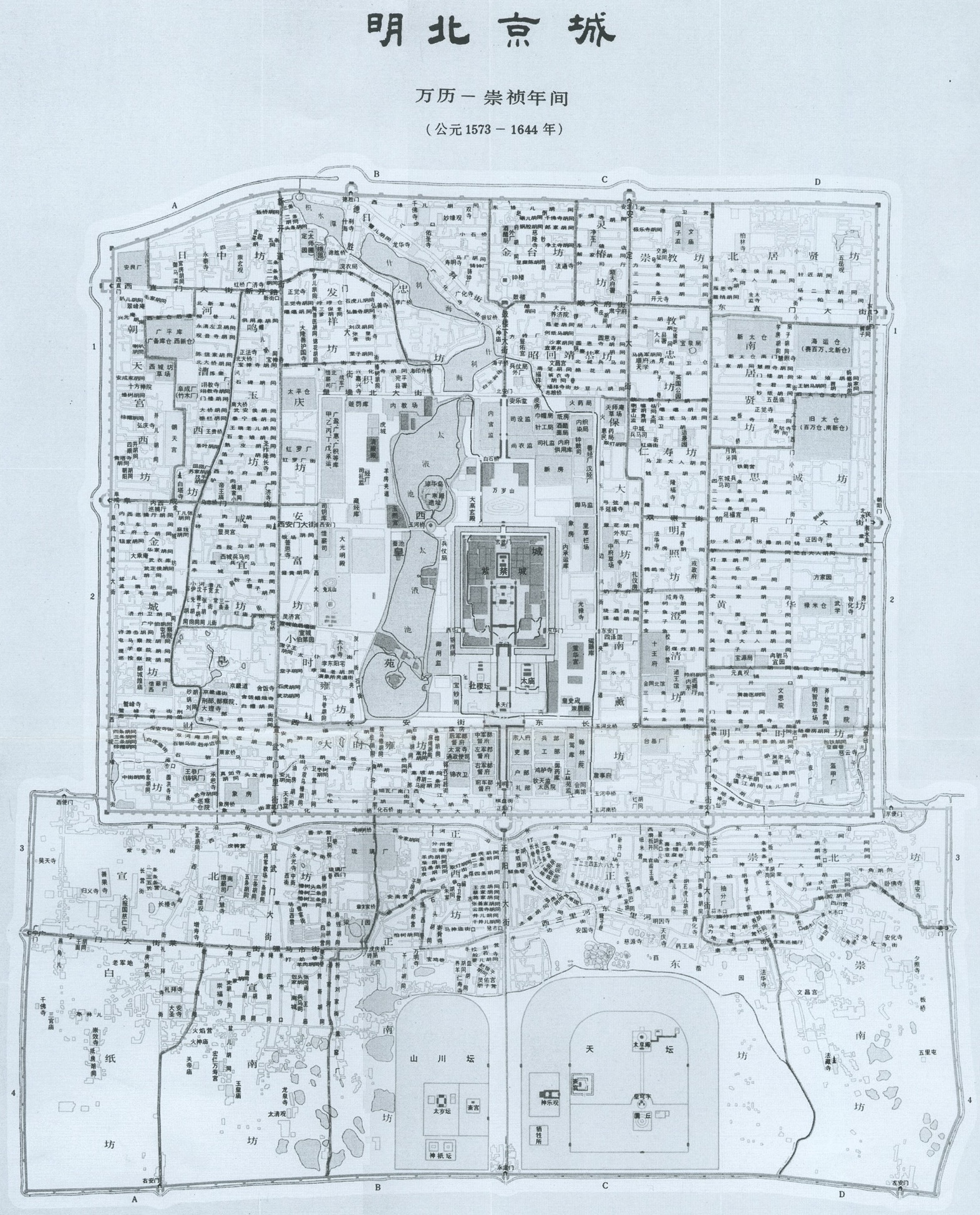

Ming Beijing Map (1573-1644)

[Photo credit]Virtual Cities Project initiated by Lyons Institute of East Asian Studies

Why does the angle matter? Beijing was considered as a sacred city, like all the capitals of previous dynasties in ancient China. Long before Beijing became China’s capital during the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368), the form and meaning of an ideal capital appeared in ancient classics such as the Zhou Li and the Classic of Poetry from the Shang and Zhou dynasties. For the emperor and his people, Beijing was the center of the world, and the universe. Every part of the city—its halls, roads, palaces, gardens, gates, and altars—was meticulously built in strict accordance with cosmic principles.

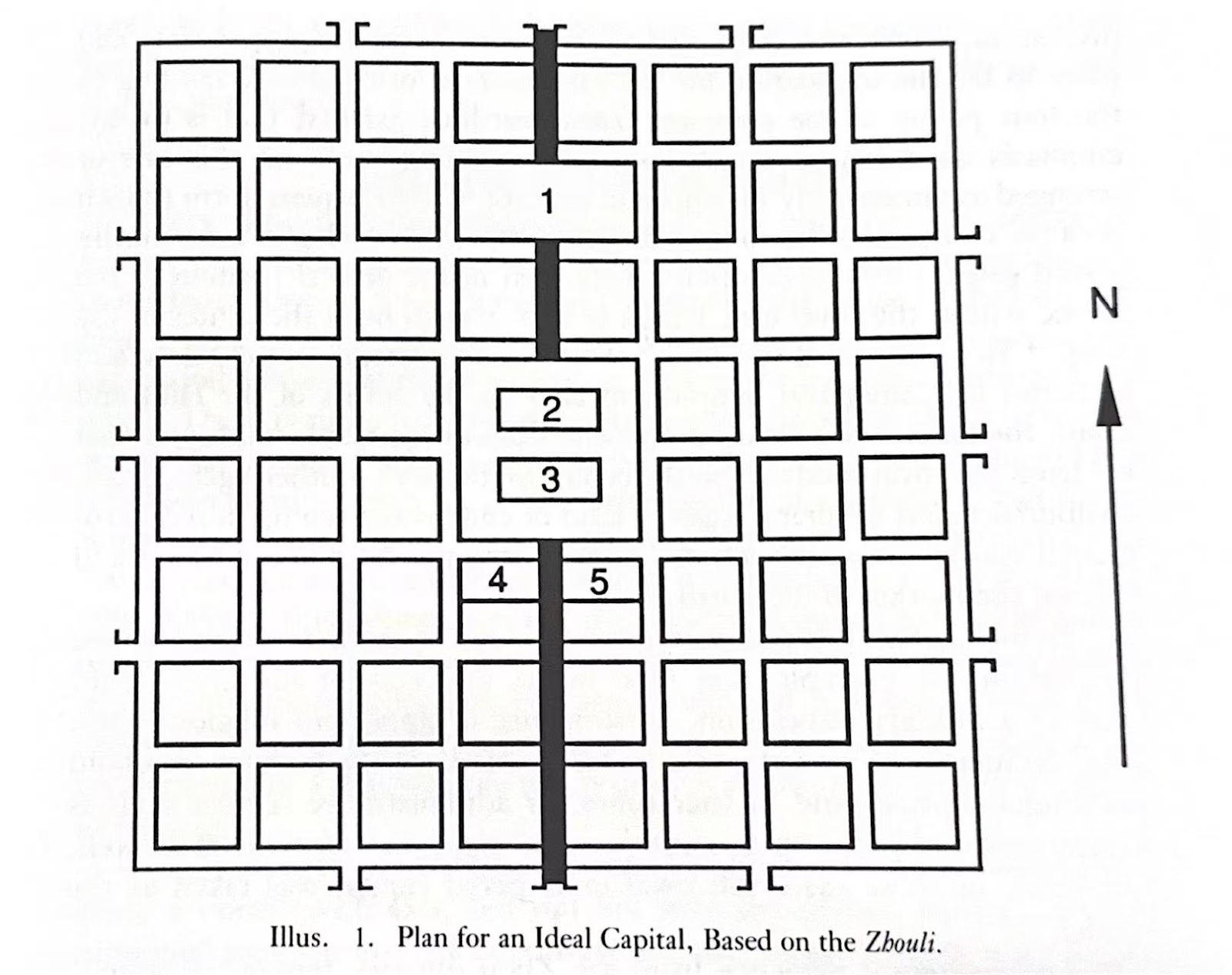

Plan for an Ideal Capital, based on the Zou Li, illustration from The Dragons of Tiananmen: Beijing as a Sacred City, page 11, by Jeffrey F. Meyer

The direction, hierarchy, symmetry, balance, and harmony in Beijing’s construction reflects principles of Chinese cosmology shared with systems of astronomy, philosophy, medicine, and feng shui. The four principal defining features of Beijing are:

- Cardinal axiality—a strong emphasis on the north-south axis. The five cardinal directions (north, south, east, west, and center) were determined based on precise observations of the pole star and the sun’s shadow, emphasizing the city’s alignment with cosmic order.

- Preparatory divination—This process involved feng shui masters and astronomers who carefully studied celestial movements, landforms, and energy flows to select the most auspicious site and time for construction.

- Square form—stability and order, shaping the city as a perfect geometric entity with the five cardinal directions.

- Concentricity—central placement of the palace within the royal city, conceptualized as the center of the Empire.

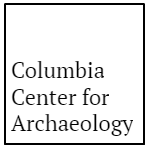

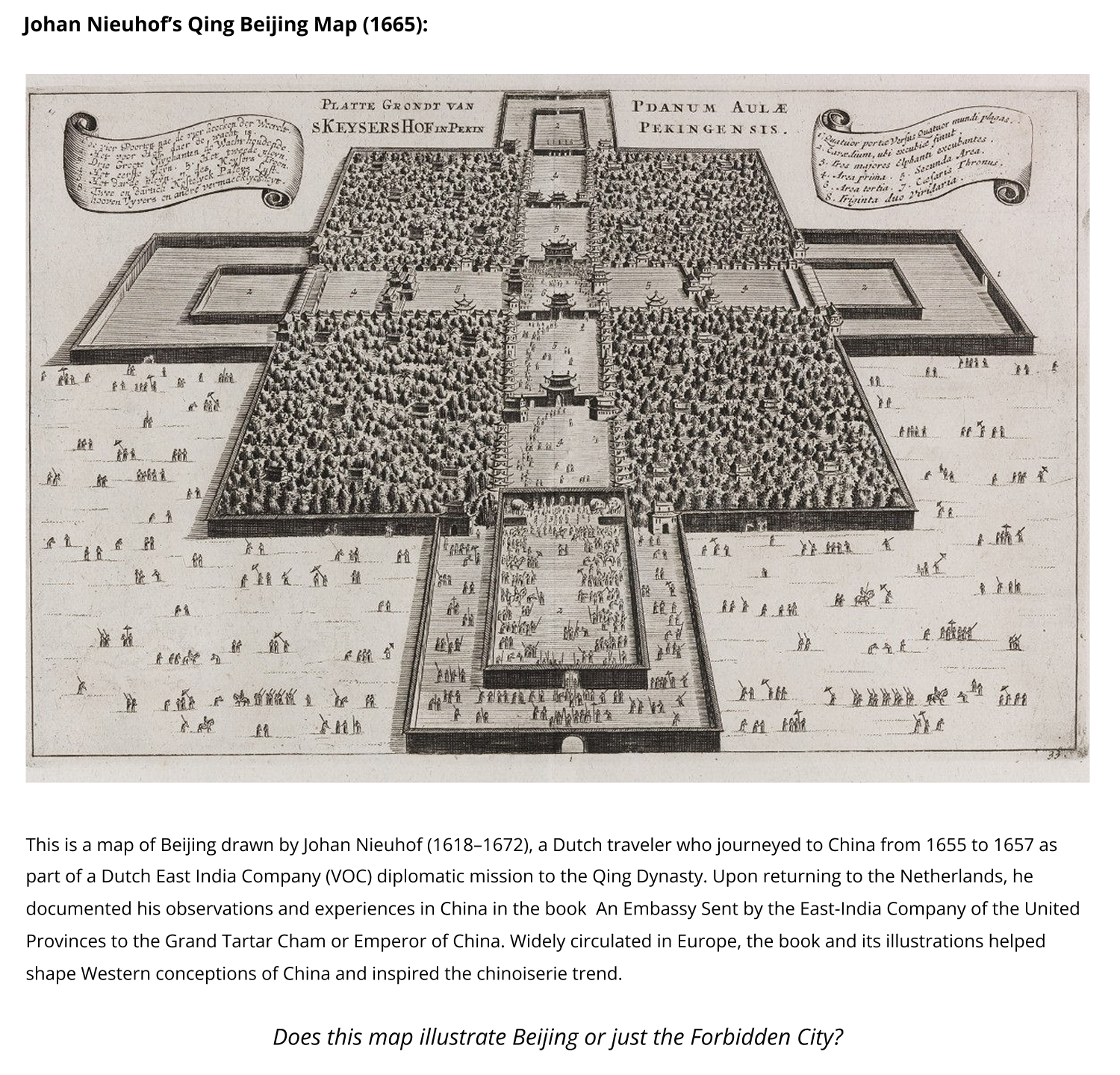

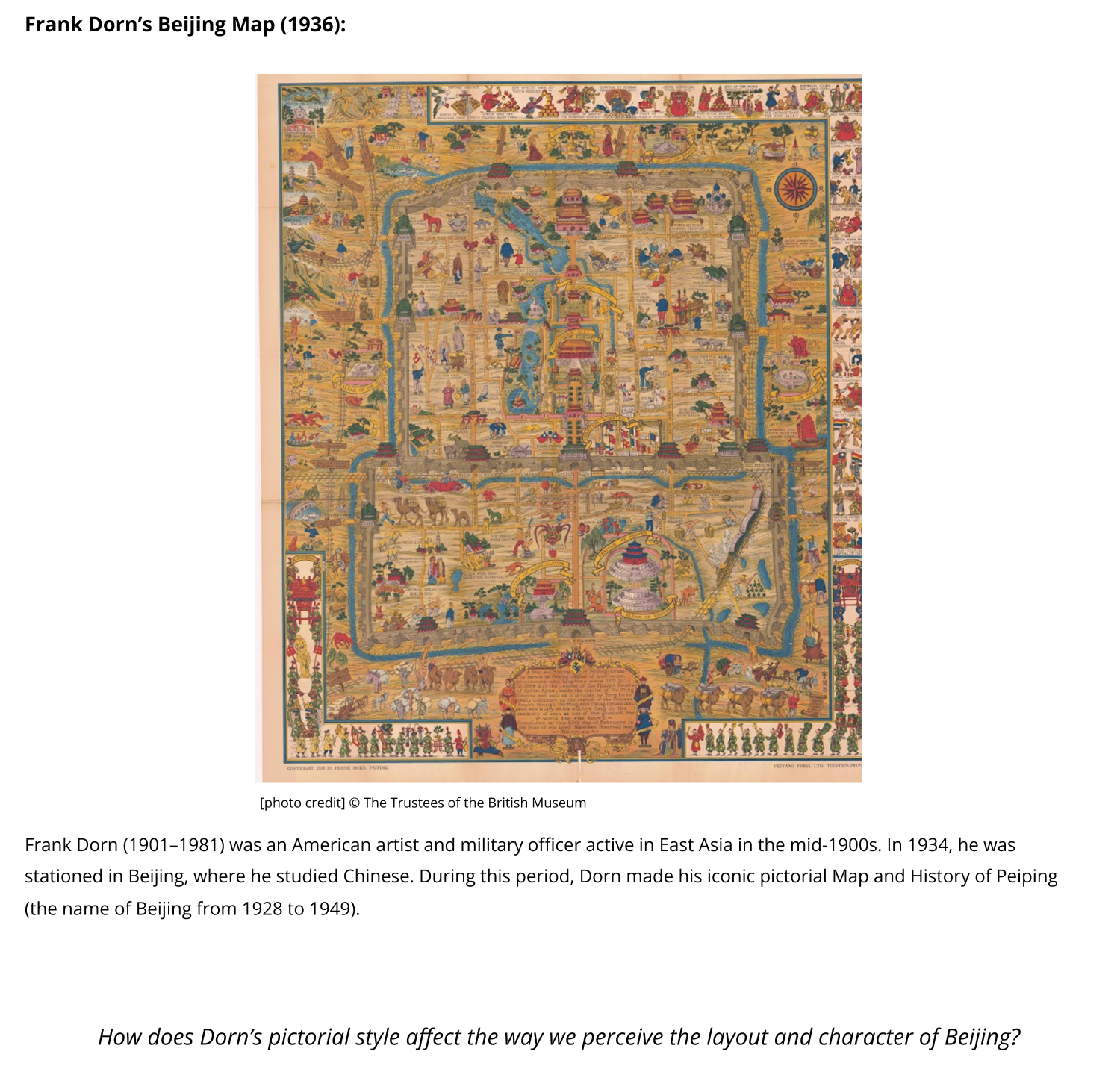

Mapping Beijing Through Western Eyes

Do you notice any differences in angle or illustration style between these maps of Beijing?

What did Beijing look like to George Campbell?

When creating the Ming Beijing (late 1400s) miniature diorama, George Campbell referred to watercolor paintings by William Alexander (1767–1816) and photographs taken during the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901)—possibly those that Bethold Laufer (1874–1934) collected for the Museum. Because these materials are from Beijing during the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), the miniature diorama does not provide an accurate representation of the earlier Ming Beijing.

William Alexander’s Watercolor Paintings

William Alexander joined Lord Macartney’s embassy to China as a junior draughtsman in 1792. Their mission was to negotiate better trading conditions for Britain in China. During Alexander’s two-year stay, he created numerous paintings depicting Chinese life, art, landscapes, architecture, and customs. Alexander’s illustrations provided one of the earliest and most detailed visual records of Qing China available to European audiences. Many of these scenes of Beijing contributed to the West’s image of the “real” Beijing.

Watercolor of Beijing by William Alexander, 1799.

[photo credit] © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Elements from the miniature diorama: gateway fortresses and bridges.

Berthold Laufer and his Chinese Expedition

In 1901, the Museum hired German anthropologist Berthold Laufer to lead an expedition to China to study Chinese culture and history. Alongside his anthropological research, he collected books, photographs, paintings, inscriptions, and artifacts. These collections, especially the photographs taken just after the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901), may have served as the primary sources for Campbell’s creation of Ming Beijing miniature diorama depicting the late 1400s.

Visit the website for more information on Lauder’s expedition to China: https://data.library.amnh.org/archives-authorities/id/amnhc_2000049

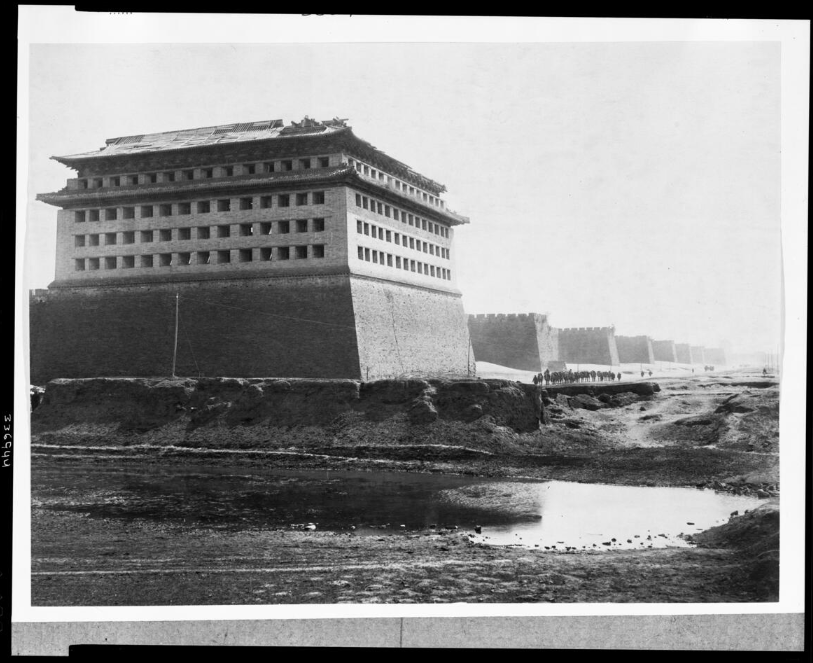

Southwest wall of Beijing, China, photographic prints collected by Berthold Laufer during the Jacob H. Schiff Chinese Expedition, 1901-1904,

[photo credit] AMNH Research Library

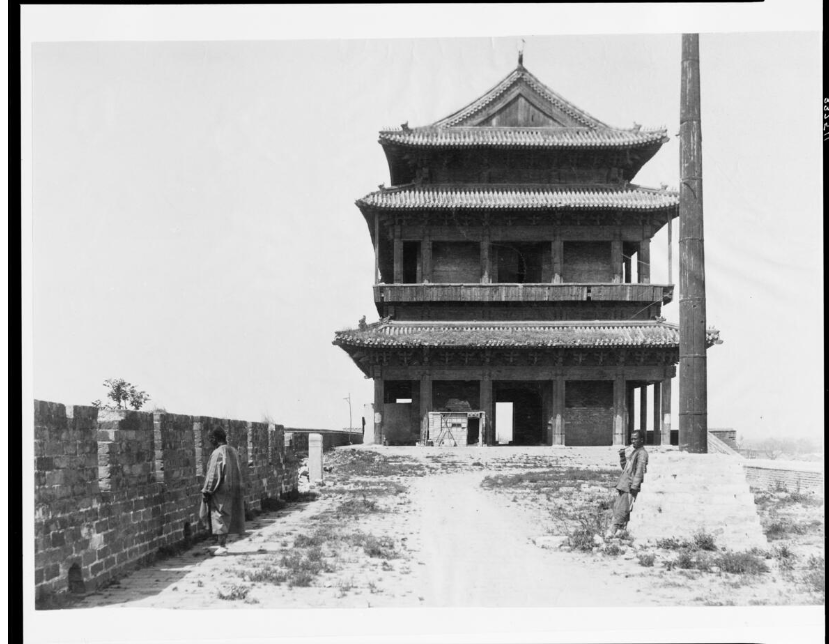

Photographs like these provide real-life references for the buildings on the city walls seen in the miniature diorama. Campbell used photographs to count the bricks to get the height of the walls for the Western Gate in the miniature diorama and to reference the fortress structure and other buildings in the miniature diorama. Again, these photographs were taken long after the Ming period (1368–1644). While they offer a way to imagine Ming Beijing, they cannot fully represent it.

Gatetower, Beijing City wall, China, photographic prints collected by Berthold Laufer during the Jacob H. Schiff Chinese Expedition, 1901-1904,

[Photo credit] AMNH Research Library

How did Ming Chinese Artists see Beijing?

Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) paintings mainly focused on the imperial court. Beijing Gongcheng Tuzhou 北京宫城图轴 (from the Jiajing reign, r. 1522–1566) depicts the Forbidden City, the restricted imperial residence of Beijing, faintly visible amidst the clouds and mist. The figure standing on the left is Kuai Xiang, a native of Suzhou and the designer of the Forbidden City during the Ming Dynasty. In the painting, officials dressed in Ming Dynasty court attire are seen bowing outside the Zhengyang Gate.

Portrait of an Official in front of the Forbidden City. 北京宫城图轴. Zhu Bang, Jiajing reign (r.1522-1566). Painted in ink and colours on silk.

[Photo credit] © The Trustees of the British Museum

Although there were few works depicted the lives of ordinary citizens, as Campbell attempts in the miniature diorama, Huangdu Jisheng Tu 皇都积胜图 (from the Wanli period, circa 1600s) offers a rare glimpse into Ming Beijing’s everyday life as a trade city beyond the Forbidden City. It illustrates marketplaces, streets, and daily activities of the residents, vividly capturing the city’s bustling atmosphere. The selected section of the painting illustrates the trade scene from Daming Gate to Zhengyang (Qianmen) Gate.

Visit the website for more information on Huangdu Jisheng Tu:

https://www.chnmuseum.cn/zp/zpml/201812/t20181218_25376.shtml

Can you see the differences in the clothing and hairstyles from those in the diorama?

What did Beijing Look Like as a Trade City?

Although most of the reference sources for the miniature diorama come from a Western perspective of Qing Dynasty Beijing, Campbell also referred to old Chinese prints to add the most crucial element to the trade city—its residents and animals. Look closely, can you find the merchants, wedding parties, jugglers, and tumblers in the miniature diorama?

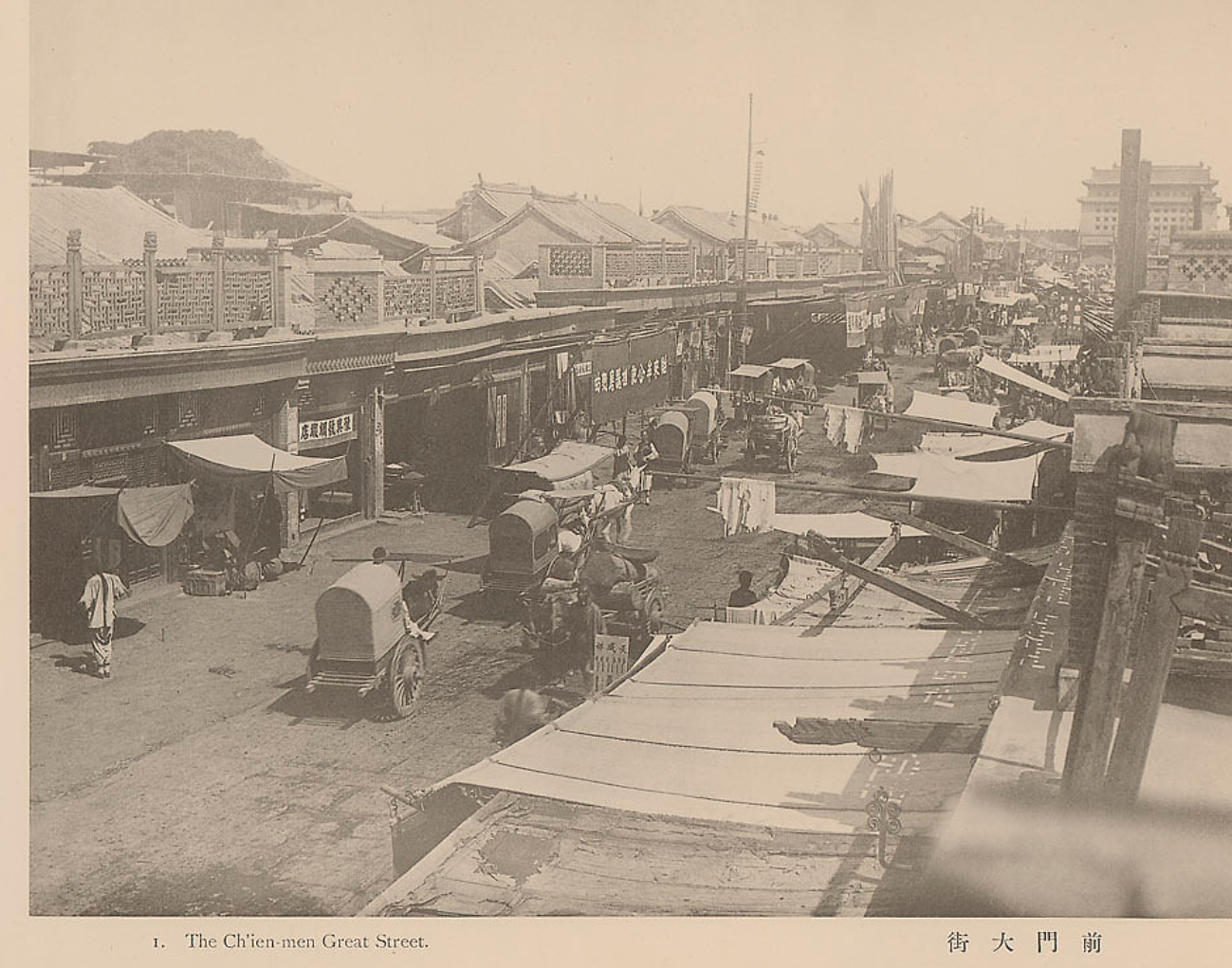

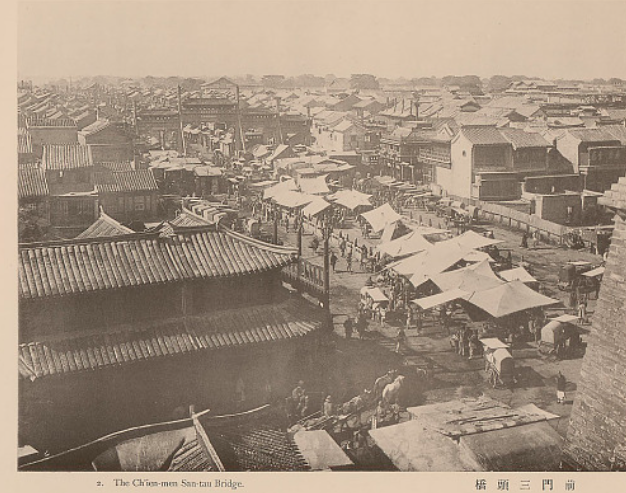

More photographs of Qing-era Beijing (1644–1911) can serve as references for imagining what Beijing as a trade city might have looked like. It is unclear why Ming Beijing was chosen to represent a trade city as a miniature diorama. While the photographs and paintings shown above may not tell us what Ming Beijing looked like, they testify to Beijing’s enduring commercial activity.

The City Today

People Walking on Street Near High-Rise Buildings During Night Time.

[Photo credit] Unsplash

Beijing stands as a pivotal global hub, balancing ancient heritage with modern ambitions. As China’s political center and economic powerhouse, it exerts tremendous influence on international trade, technology development, and geopolitical affairs. The city’s strategic importance continues to grow as it shapes global governance structures and economic patterns through initiatives like the Belt and Road, redefining East-West relations.

Is this a Western Gaze?

Campbell used materials from Qing-era Beijing to create the Ming Beijing miniature dioramas, primarily because these were the most accessible resources to him. However, the selection of sources is never neutral; here they shaped an image of a timeless China for Western audiences—just as William Alexander’s watercolor paintings did. China as seen through the eyes of a British embassy came to stand as the real China.

We need to rethink the miniature diorama and the process of creating it. While it serves as an educational tool for museum audiences to learn about Asian culture—one they may not have the chance to visit in person—it also constructs a representation of the “Other,” a cultural reality of its own.

References:

Campbell, Aurelia. 2020. What the Emperor Built: Architecture and Empire in the Early Ming. University of Washington Press.

Meyer, Jeffrey F. 1991. The Dragons of Tiananmen: Beijing as a Sacred City. Studies in Comparative Religion. University of South Carolina Press.

Wan, Ming. 2025. Ming-Dynasty China and the World Along the Silk Road. Routledge, Routledge Studies in Chinese History.