Isfahan اصفهان: Half the World (1501-1722)

Welcome to Isfahan

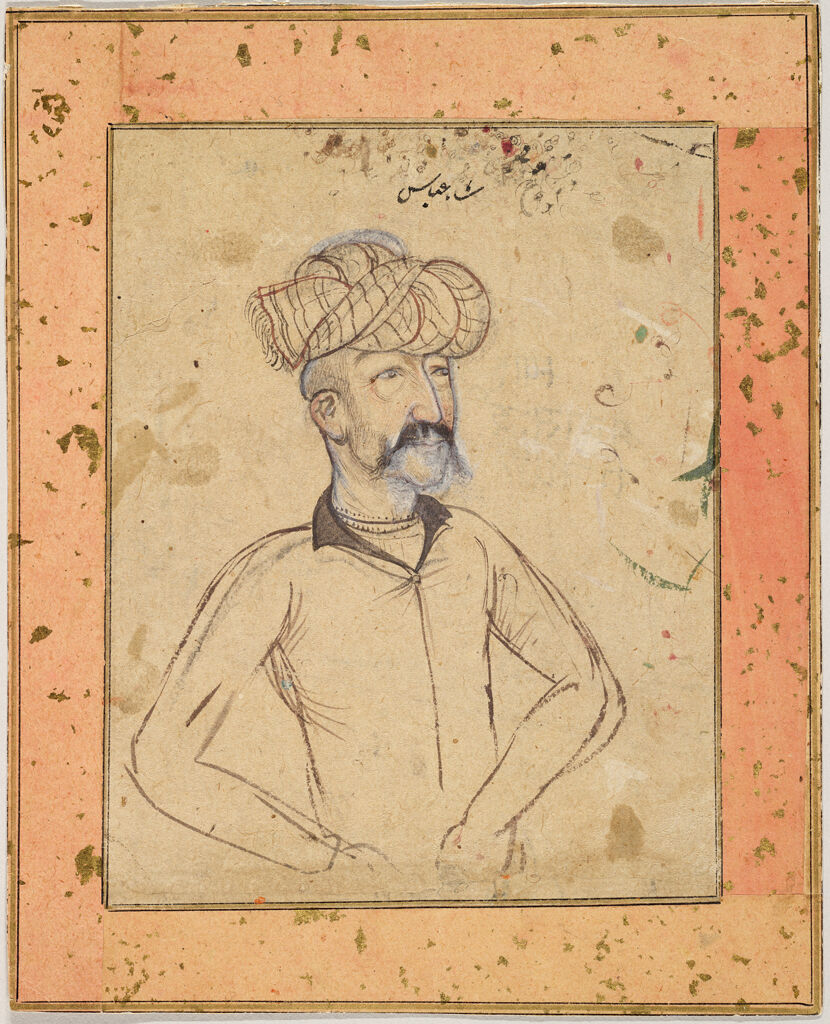

The Safavid Dynasty used Isfahan, previously nicknamed “Half the World,” as its seat of power to rule Iran (Persia) from 1501–1722. Shāh ‘Abbas I consolidated power and catapulted Isfahan into its prime as a trade city.

How to Play:

1. Find Hidden Objects – Look at the photo of the miniature model. Using the Object List for reference, locate the objects with your cursor.

2. Hover for Info – Hover over an object to see an enlarged image and a short description.

3. Learn More – Some objects link to themed sections on the city. Click “Learn more!” to scroll down for more details.

4. Use the REVEAL Button – Stuck? Click REVEAL to turn the invisible rings red and access the pop-ups directly.

How to Play:

1. Find Hidden Objects – Look at the photo of the miniature model. Using the Object List for reference, locate the objects.

2. Click for Info – Click an object to see an enlarged image and a short description.

3. Learn More – Some objects link to themed sections on the city. Click “Learn more!” to scroll down for more details.

4. Use the REVEAL Button – Stuck? Click REVEAL to turn the invisible rings red and access the pop-ups directly.

Object List

Polo Goalposts

Camels

Carpets

Naqsh-e Jahan Square

Zayandeh Rud

Royal Mosque

Flying Carpet

Royal Mosque

The historic Royal Mosque (Masjid-e Shah), now called the Imam Mosque, is located at a different angle to

the rest of the square. This orientation allows Muslim followers to face Mecca while they pray.

Want to learn more about religion in Isfahan?

Polo Goalposts

Polo (in Persian, chogān) was invented in Central Asia over 2,000 years ago. Built in the 1600s, these stone

goalposts are some of the oldest remaining in the world. Chogān is still played here in Naqsh-e Jahan Square

during special events and festivals.

Want to learn more about ongoing cultural traditions in Isfahan?

Carpets

Carpets: Hand-woven Iranian carpets served practical function and acted as artistic symbols of wealth in

Safavid Iran. They are just one of many products that were manufactured, bought, and sold in the bazaars of

Isfahan.

Want to learn more about ongoing cultural traditions in Isfahan?

Camels

Camels were used for riding and transporting goods along the Silk Road routes. Some of the goods that camels

carried, such as coins, paper, silk, and spices, arrived from Beijing.These animals

are strong and sturdy and can go for long periods without food and water in Iran’s desert. Camels’ prominent

role in desert environments led them to become symbols in myths and religious practices in Islamic culture.

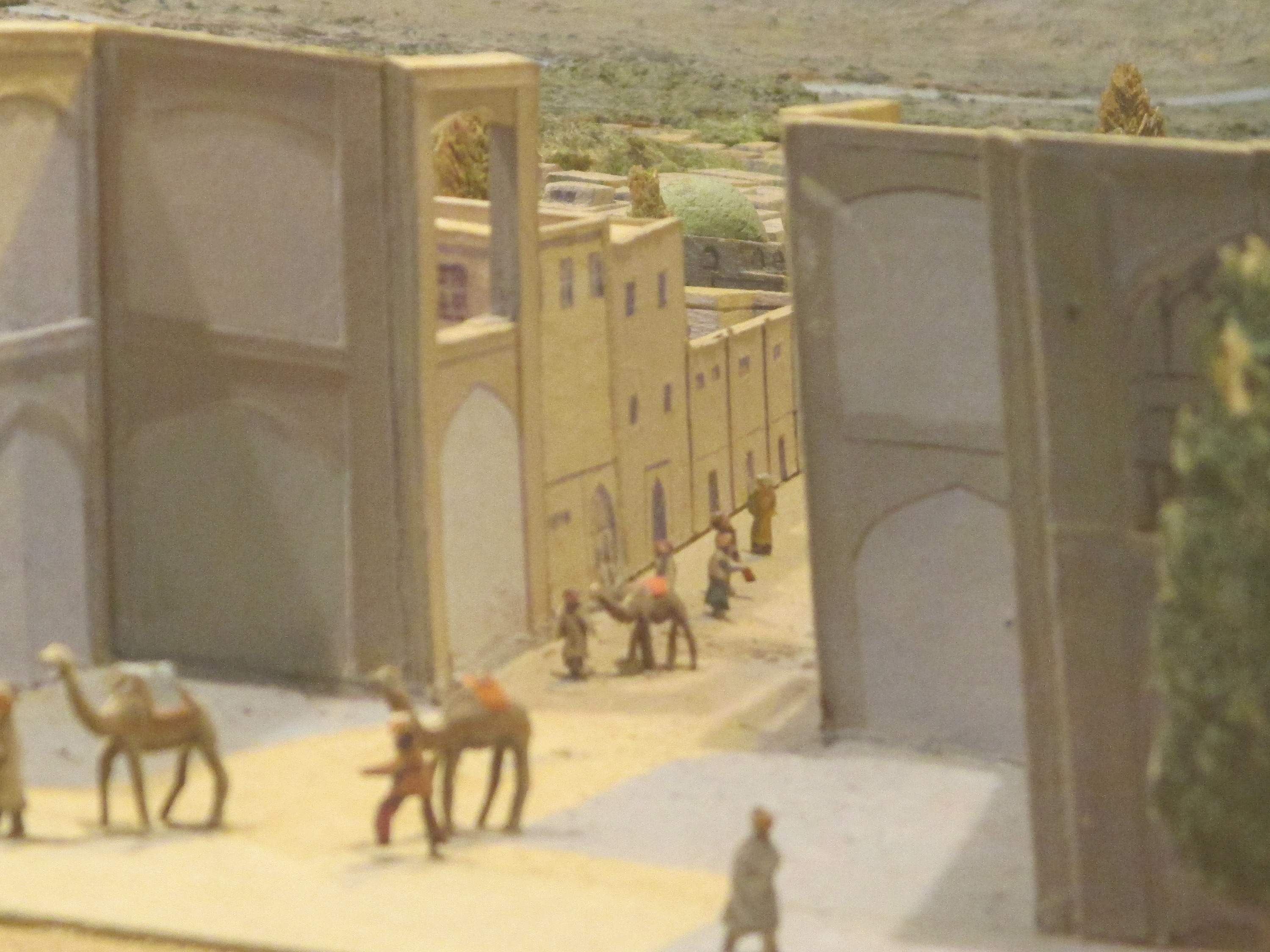

Naqsh-e Jahan Square

In the 1600s, this would have been a gated access to private living quarters of the Shāh’s female relatives.

Today, it is one entrance to Isfahan’s famous Naqsh-e Jahan Square, now known as the Meidan Emam. Built

under Under Shāh ‘Abbas I in the early 1600s, it is one of the largest city squares in the world. The south

end of the Naqsh-e Jahan, featuring the Royal Mosque, is depicted in the diorama.

Want to learn more about the architecture of Isfahan?

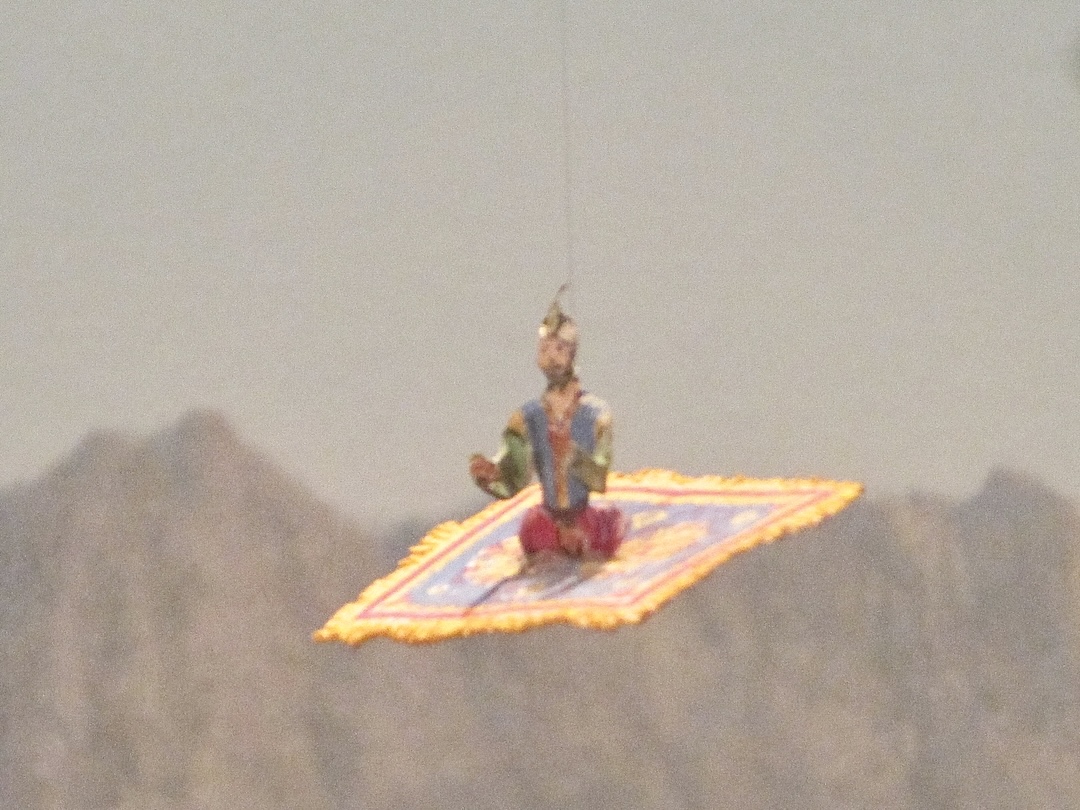

Flying Carpet

This is a flying carpet, which may speak to the literary history of Isfahan. However, an artist’s decision

can entrench stereotypes in their work.

Want to learn more about Orientalism?

Zayandeh Rud

The 215-mile (346-km) fertile river flowing through Isfahan is the source of much of the city’s prosperity. The Zayandeh Rud receives water from melting snow from mountains such as the Zagros pictured in the diorama. More than 5,000 feet above sea level on the Iranian Plateau, Isfahan averages only 5 inches of rainfall per year.

REVEAL

Portrait of Shah ‘Abbas I, attributed to Mughal court painter Bishndas, circa 1617

[Photo credit] Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of Stuart Cary Welch, Jr., Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College, 1999.304

The Oriental Gaze

“Orientalism” describes a harmful misunderstanding of Asian and North African cultures that portrays people and places as timeless and unchanging by wrongfully merging different geographies, time periods, and traditions. Reducing entire groups to objects of scientific study leads to incorrect representations, such as the inclusion of the flying carpet in the Isfahan diorama. This fantastical element encourages visitors to view Isfahan as a place of mysticism, perpetuating racism by reducing lived experiences to exotically imagined stereotypes.

Close-up photograph of flying carpet,

[photo credit] Celene Lignell, 2025

This is the controversial flying carpet in the miniature diorama. What details of the carpet and person riding it can you see?

The Flying Carpet

The idea of the flying carpet originated as early as the 800s in the popular Islamic Golden Age story collection, One Thousand and One Nights, and the motif has since appeared repeatedly in popular culture. For example, you may recognize the carpet from the 1992 Disney movie Aladdin. Although its literary roots are well known, the inclusion of the flying carpet in the Isfahan miniature diorama can perpetuate a stereotyped understanding of Isfahan and distract from the city’s vibrant culture. The addition of a fantasy element in this diorama contributes to an ongoing perception of Iran as an unchanging place of mysticism rather than an innovative cultural and scientific hub.

Campbell’s Inspirations

According to archived exhibition notes, miniature constructor George Campbell (Link to Behind the Construction on miniature website) used photographs supplied to him by the Iranian Tourist Office, along with prints from the 1600s as his main sources for the Isfahan miniature. He also referenced a diagram of the Royal Square from Anthony Welch’s 1973 Asia House Gallery exhibition catalogue, Shah ‘Abbas & the Arts of Isfahan. You can see Welch’s diagram both on the label deck of the actual miniature diorama and in the architecture section of this website.

Life and Culture in Isfahan Under the Safavid Dynasty: Learn More!

Isfahan’s Markets

Isfahan was a significant city in global trade networks in the 1600s. The city was known for its textiles—a key feature in mosques, bazaars, and government buildings since the 900s. Can you see these carpets in the diorama? The markets also sold desirable food goods such as salep—a flour made from orchids— and the entirely novel commodities of coffee and tobacco. With global connections, the religiously diverse population of Isfahan transported these goods around the world.

Literature

Isfahan was a center of poetic creation where poets writing in Arabic implemented well-known devices such as rhythm and rhyme patterns. Later, in the early-modern period (1500-1700), many of Isfahan’s writers relocated to other places including, eventually, Kolkata because Shāh ‘Abbas I did not see literary art as profitable in Isfahan’s booming trade market. Writer Mir Muhammad Mansur Semnani (Ashiq) (d. 1732) expressed this experience through poetry in “Guide to Strolling Through Isfahan”:

“Whenever my weary mind reminisces on

Isfahan.

Being distant from friends and deprived of

strolling (sayr) on the Chaharbagh

Is extremely hard, may God ease it for Ashiq.”

A more popularly recognized piece of literature written well before “Guide to Strolling Through Isfahan” is One Thousand and One Nights. This famous collection of tales was originally written in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age (750-1258). “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp” and “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves” are well-known stories in Western culture. However, these two stories were added by French archaeologist Antonie Galland, who translated the collection from Arabic to French in the 1700s and made it available to a Western audience for the first time. Many other Arabic and Persian language texts have yet to be translated into English.

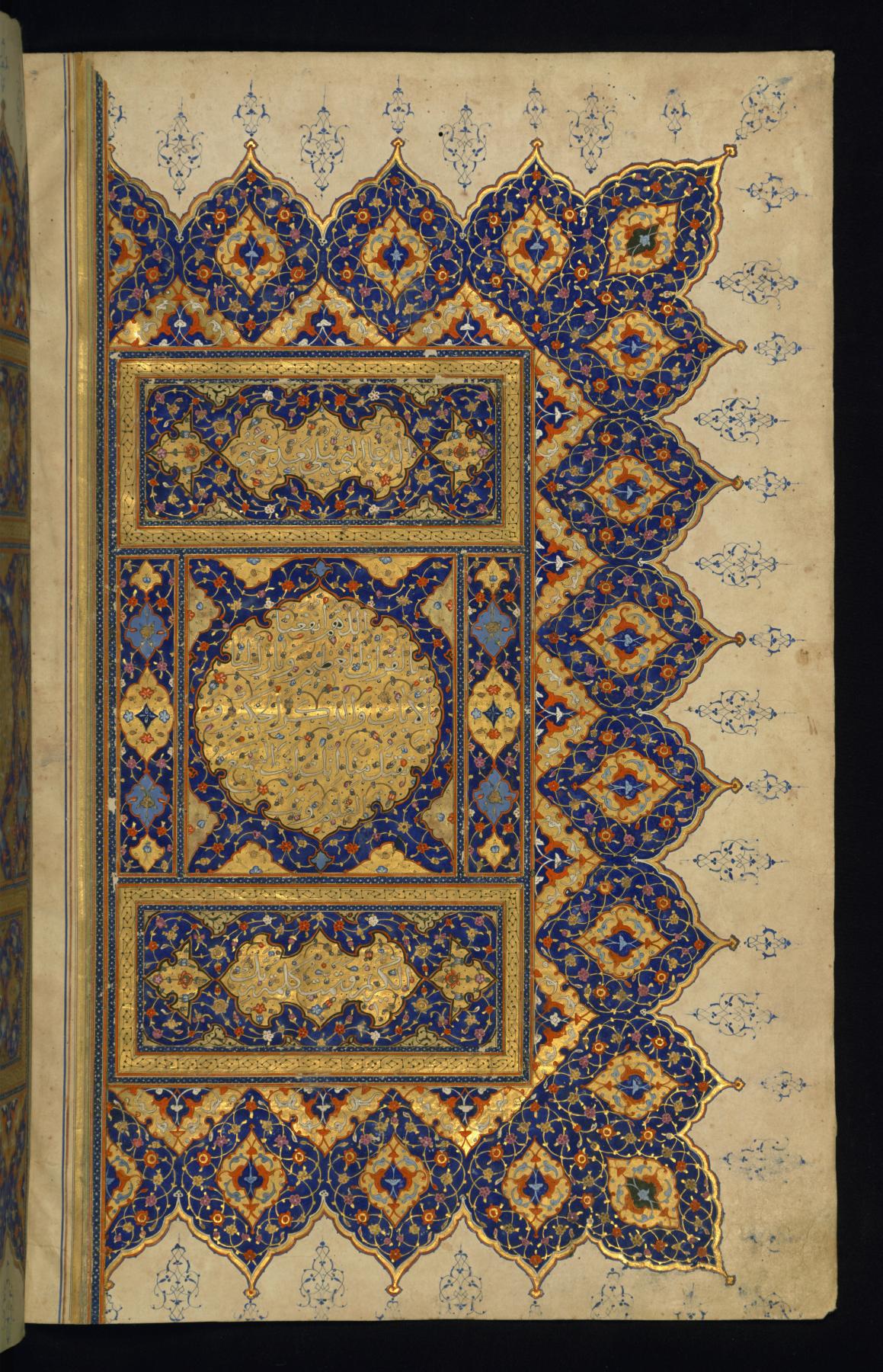

Lower board inside flap from Collection of poems (divan). Inscribed by Shah Mahmud Nishaburi in 16th Century Iran.

[photo credit] Courtesy of The Walters Art Museum, acquired by Henry Walters, W.640.

Religion and Cosmology

Did you know that Isfahan was a major trade city for Christian, Muslim, and Jewish communities alike? Zoroastrianism, one of the oldest religions in the world, also originated in Iran. At the start of the 1500s, Isfahan was a religiously diverse city. Iranian astronomers and philosophers created theories about how the planets, moon, sun, and stars were oriented in the universe. Inspired by the work of Greek mathematician Ptolemy, these theorists organized the world into seven sections, or climata, and situated Isfahan at the center of the fourth. Although the origins of the nickname “Half the World” are unknown, this understanding of the cosmos influenced ideas about the geography of Isfahan. As merchants in Isfahan created strong trade networks, members of local Islamic groups, migrant Armenian Christians, and long-established Jewish communities interacted frequently and were central to the prosperity of the city. In the 1600s, when the miniature diorama is supposedly set, one would have been able to Armenian Christian neighborhoods near the river due to the Shah’s attempts to further exploit their trade connections through forceful relocation.

Right Side of an illuminated Finispiece with Inscribed Prayer from Qur’an. 17th Century (Safavid).

[photo credit] Courtesy of The Walters Art Museum, acquired by Henry Walters, W.569.331B.

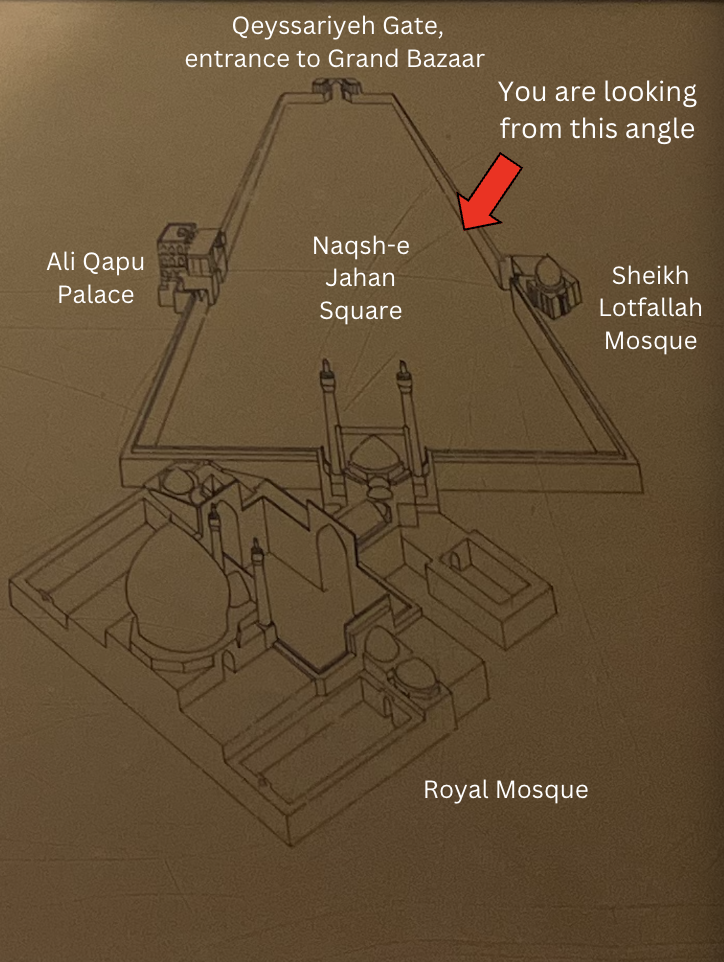

Architecture

The Naqsh-e Jahan Square, translated as “Image of the World” Square, is depicted both in the miniature diorama and in Anthony Welch’s diagram below. The square, crafted by architect Ali Akbar Isfahani and others, has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site for its outstanding value to humanity. Constructed as part of Shāh ‘Abbas I’s urban development campaign in the 1600s, the Naqsh-e Jahan has been a site of political gatherings, polo matches, and trade. The square is framed by monumental architecture on all sides: the Ali Qapu Palace, the Qeyssariyeh Gate, the Sheikh Lotfallah Mosque, and the Royal Mosque. Each building is renowned in its own right, and together they create a remarkably symmetrical site. Look closely at the beautiful blue tiles and vaulted ceiling ornamentation, both classic features of Safavid Iranian architecture.

Anthony Welch’s diagram from the Isfahan label deck with orienting descriptions

[Photo credit] Adele Roulston, 2025

Close-up image of the intricate design on the entrance to the Royal Mosque

[Photo credit] ©UNESCO, image taken by Francesco Bandarn, 2006, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.9 IGO

Isfahan Today

2018 polo match in Naqsh-e Jahan Square with the Royal Mosque (scaffolded for construction and upkeep) visible in the background

[photo credit] ©Hamidreza Nikoomaram, 2018, Creative Commons

Recommended Readings

Isfahan: Architecture and Urban Experience in Early Modern Iran (2024) by Farshid Emami

Orientalism (1978) by Edward Said