Kolkata: A City Hidden (1750-1800)

Welcome to Kolkata

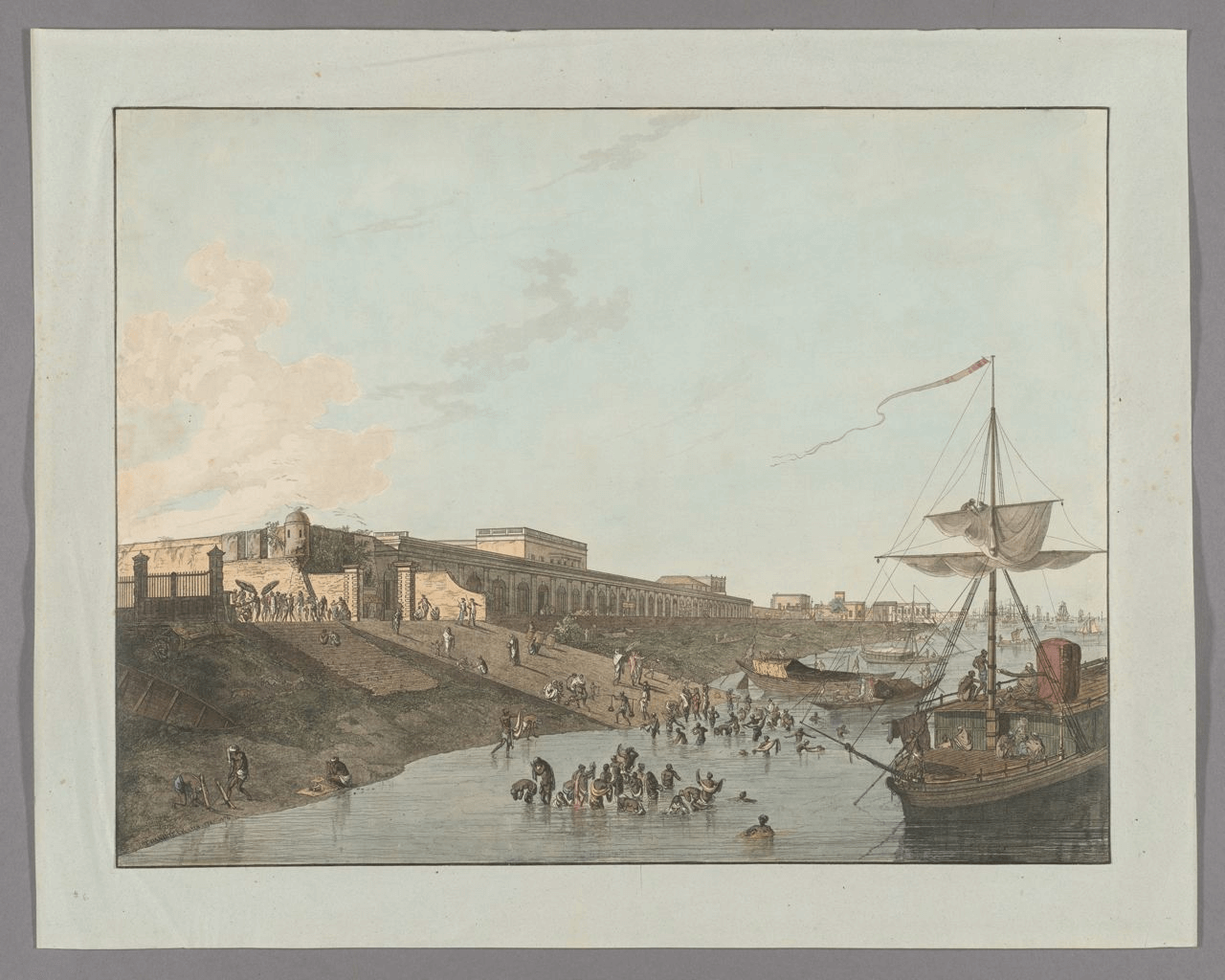

In the late 1700s, the Indian Bengali city of Kolkata became the seat of power of the British East India Company, the largest trading company of the Western world. Viewing this miniature diorama from the cabin of a ship, museum visitors share the privileged vantage point of a potential captain or other high-ranking personnel of the Company. This perspective exposes the invasive power the Company wielded over the landscape and ultimately clouds Kolkata as a hidden city. Let’s explore along the shore.

How to Play:

1. Find Hidden Objects – Look at the photo of the miniature model. Using the Object List for reference, locate the objects with your cursor.

2. Hover for Info – Hover over an object to see an enlarged image and a short description.

3. Learn More – Some objects link to themed sections on the city. Click “Learn more!” to scroll down for more details.

4. Use the REVEAL Button – Stuck? Click REVEAL to turn the invisible rings red and access the pop-ups directly.

How to Play:

1. Find Hidden Objects – Look at the photo of the miniature model. Using the Object List for reference, locate the objects.

2. Click for Info – Click an object to see an enlarged image and a short description.

3. Learn More – Some objects link to themed sections on the city. Click “Learn more!” to scroll down for more details.

4. Use the REVEAL Button – Stuck? Click REVEAL to turn the invisible rings red and access the pop-ups directly.

Object List

Governor’s Yacht

British East India Company Flag

Life-saving apparatus attached to ship

Fort William

River

River boat

Governor’s Yacht

This is the governor’s yacht—it remained stationed on the water to showcase Britain’s prowess. Warren Hastings served as the governor-general from 1773 to1785, the time period represented by this diorama.

British East India Company Flag

This is the flag of the Company, and it would have been a common sight on each of their ships. Does it look familiar? The Grand Union Flag, used by the Thirteen Colonies from 1775 to 1777, bore a striking resemblance to it. Some historians claim the similarity between the flags speaks to the North American colonists’ initial loyalty to the British Crown and their desire to self-govern in the same manner as the Company.

Life-saving apparatus attached to ship

This wooden flotation device was one of the earliest life-saving apparatuses found on a ship. Campbell was fascinated by the history of ship building and created many of his own detailed diagrams of historical ships. Including the flotation device exemplifies his knowledge of ships.

Fort William

This is the second Fort William built in the city of Kolkata after damage during a battle destroyed the first in 1756. This fort served as the military base and trading station for the British East India Company.

Want to learn more about the rise of the Company in Kolkata?

River

The Hooghly River connects Kolkata to the ocean via the Ganges. The Hooghly is a major waterway for trade, and the land alongside the river is extremely fertile. The Hooghly is revered by Hindus as the Ganges’ most sacred tributary.Want to learn more about the Kolkata port today?

River Boat

This river boat, made by the boatcrafters of Kolkata, would have been present alongside the ships of the British East India Company. These boats were used to transport passengers and goods between the shores of Kolkata and larger ships that could not stop closer to land.

Creative Liberties

Surviving notes indicate that Campbell used prints and drawings as inspiration for his miniature creation. The Company ships featured in this scene, called “East Indiamen,” were modeled from ship drawings found at the National Maritime Museum in London. Additionally, archived correspondence demonstrates a request for prints of India from the India Office Library from both the 1700s, a period of time when Europeans circulated stereotypes of the lands and people of Asia, and from the 1970s, when Campbell built the diorama. He may have never been to Kolkata nor collaborated with anyone who had; the miniature is Campbell’s artistic view of what the city was like in the 1700s. Click through a slideshow of prints!

Simms, F. W., Thuillier, H. L., Smyth, R. & J. & C. Walker. (1857) Map of Calcutta from actual survey in the years -1849.

[photo credit] The Library of Congress

After the Anglo-Dutch wars (1652–1784), Britain claimed India as a sphere of interest. Acting independently from the Crown, the British East India Company was already aggressively interfering with Gujarati textile trade. To expand their influence, they purchased three villages from the Mughal Empire in 1698—Kalikata, Gobindapur, and Sutanuti—creating colonial “Calcutta.” The Company solidified its hold on Kolkata after the Battle of Plassey in 1756, following conflicts and allyships between itself, the Mughal Empire, and the Maratha Empire. The Battle of Plassey occurred between the Company and the Nawab of Bengal, an independent ruler of the fragmented Mughal Empire. As the last powerful opposition to the Company in Kolkata, the Nawab’s strength in the city, and the greater region of Bengal, was greatly weakened after the battle. Assumptions that solely credit the British presence for Kolkata’s prosperity disregard the local history of the area, urging us to reconsider its colonial depiction in its miniature diorama.

A Western artist’s imagining of Shah ‘Alam, Mughal Emperor (1759–1806), Conveying the Grant of the Diwani to Lord Clive, August 1765, c.1818.

[photo credit] The British Library

This miniature diorama offers a view of Kolkata from inside a British East India Company trading ship. This perspective showcases the Company’s power over the city—as we are looking from the view of the colonizer, this becomes a physical representation of British colonization. Placed on the ship, we view Kolkata through the privileged eyes of high-ranking personnel, who would have had a very different perspective on the city than the local communities.

Empire’s Gift or Empire’s Grip?

A Portrait of an Influential Indian Reformer, Unknown Author, (1833).

[photo credit] The British Library Archive.

If the diorama only showcases the perspective of the British East India Company, what about the people of Kolkata? As the strength of the Company’s influence grew in the late 1700s, the social landscape of the city changed. The traditional merchant groups of Kolkata, who specialized in cotton goods and spices, were strategically pushed out in favor of Indian merchants whose trade benefited the Company. This ultimately led to divisions in the city between the elite English, a more diverse city center with global trading connections, and an increasingly disadvantaged laboring class of locals from Kolkata.

In the late 1700s, a socio-religious and political movement called the “Bengali Renaissance” arose. This movement created a discourse of European ideas through Hindu literary and artistic traditions. Though more emphasis was purposefully placed on the Bengali language, discussions happened in both English and Bengali, demonstrating the cultural exchange between English and Bengali scholars. This discourse would eventually help form an Indian national identity independent of colonial control.

Kolkata Uncontained

A Photo of Indian River Boats Alongside Fort Williams’ Bank, 2023

[photo credit] Unsplash/Aashish Singh

This photograph transports us beyond the limited perspective of the diorama, taking us ashore to witness Kolkata as it is today, a city that has taken on a new identity. In 2001, the state government changed the city’s name from the anglicized Calcutta to Kolkata, to reflect Bengali pronunciation. As of 2024, the famous Fort William, once a symbol of British military control, is Vijay Durg, the headquarters of the Indian Army’s Eastern Command. The historical port was renamed Syama Prasad Mookerjee Port in 2021, reflecting a reclaimed national identity. It has since achieved unprecedented success, handling a record-breaking 66.45 million metric tonnes (MMT) of cargo in 2023–2024—the highest traffic in its history. These renamings embody a shifting narrative, asserting Kolkata’s resilience and transformation. Even though local efforts preserve the city’s layered history and ensure that its colonial legacy is acknowledged, one thing is certain: this history no longer defines its present or future.

Recommended Readings

The Anarchy: The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an Empire (2019) by William Dalrymple

Empire of Cotton: A Global History (2015) by Sven Beckert