Ainu: From Cast to Case

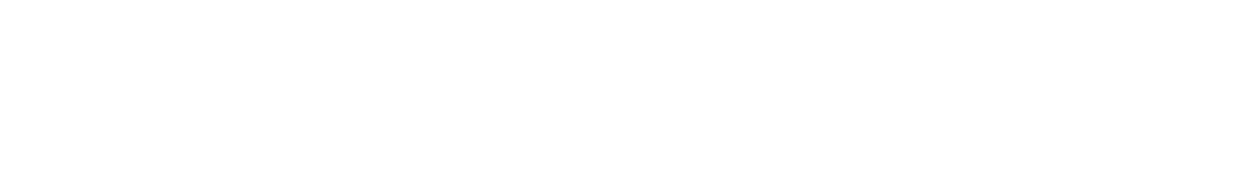

The three mannequins in the AMNH’s Ainu case, AMNH

Who are these mannequins modeled after?

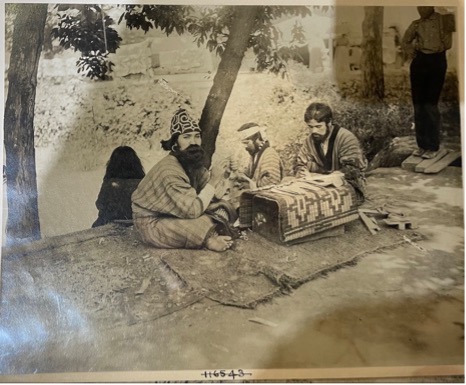

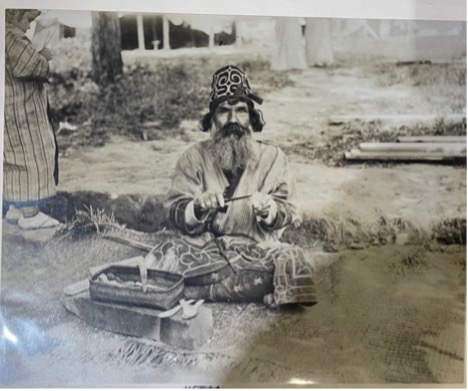

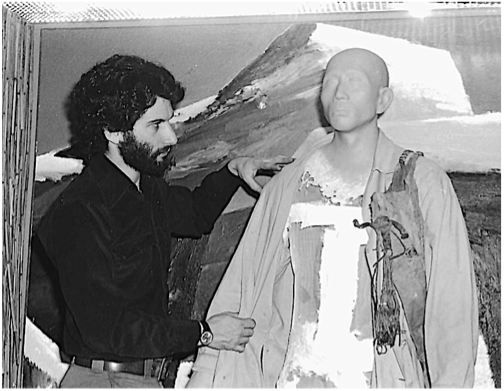

In 1904, Pete Gorō, Shirake and Ozara Fukotaro (also known as Yazo) arrived in St. Louis, Missouri as part of the Ainu group for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. Like most world’s fairs of the time, the Exposition featured an anthropology department where visitors could walk through an open space and view various indigenous peoples as they lived their “daily lives”. The Ainu group constructed a home, wove baskets, competed in archery and performed various ritual and daily activities for the audience. After the Exposition, following a then-common anthropological practice, AMNH commissioned sculptor Casper Mayer to create life casts of Pete Gorō, and Shirake and Ozara Fukotaro. Over fifty years later, long after they had returned home to Hokkaido, sculptor Eliot Goldfinger used those casts as models for the Ainu mannequins housed in AMNH’s Hall of Asian Peoples.

A glimpse into the Ainu group’s time at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition

Slideshow of photos

Library Special Collections, AMNH

What was the intent behind these mannequins?

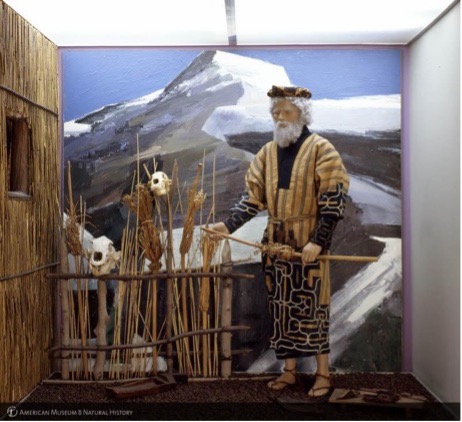

Eliot Goldfinger, sculptor and creator of the Ainu and Semai mannequins, designed the Ainu figures to be support forms for traditional Ainu clothing and artifacts. Rather than trying to faithfully represent real people, Goldfinger and the curatorial team chose to make the mannequins more abstracted by leaving out facial details, They believed this made the figures less intrusive and controversial than lifelike representations would have been. According to Goldfinger, the Ainu mannequins represent an “idealized and stylized” version of a person, rather than a realistic depiction.

Sculptor Eliot Goldfinger with Ainu Mannequin

AMNH courtesy Eliot Goldfinger

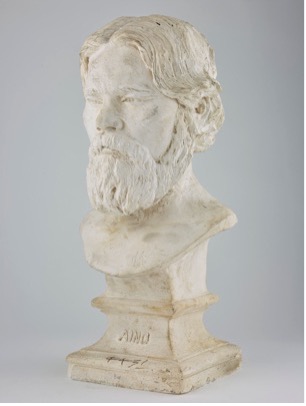

See Casper Meyer’s detailed life casts…

Division of Anthropology, AMNH

Can you find these Ainu artifacts in the AMNH cases?

Bow (70/64)

Comb of hand loom (70/4127)

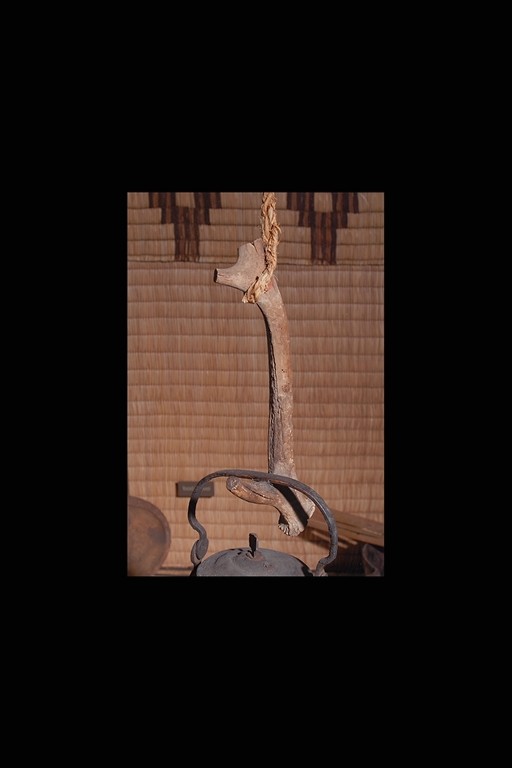

Ainu kitchen hook (deerhorn) for hanging kettle (70/4075)

Spoon: large, wood (70/4080)

Mallet for breaking food before cooking (70/4081)

Ceremonial platter for feeding bear (70/4155)

Pestle for crushing corn (70/4084)

Food platter (70/4068)

Why does the female mannequin have a facial tattoo?

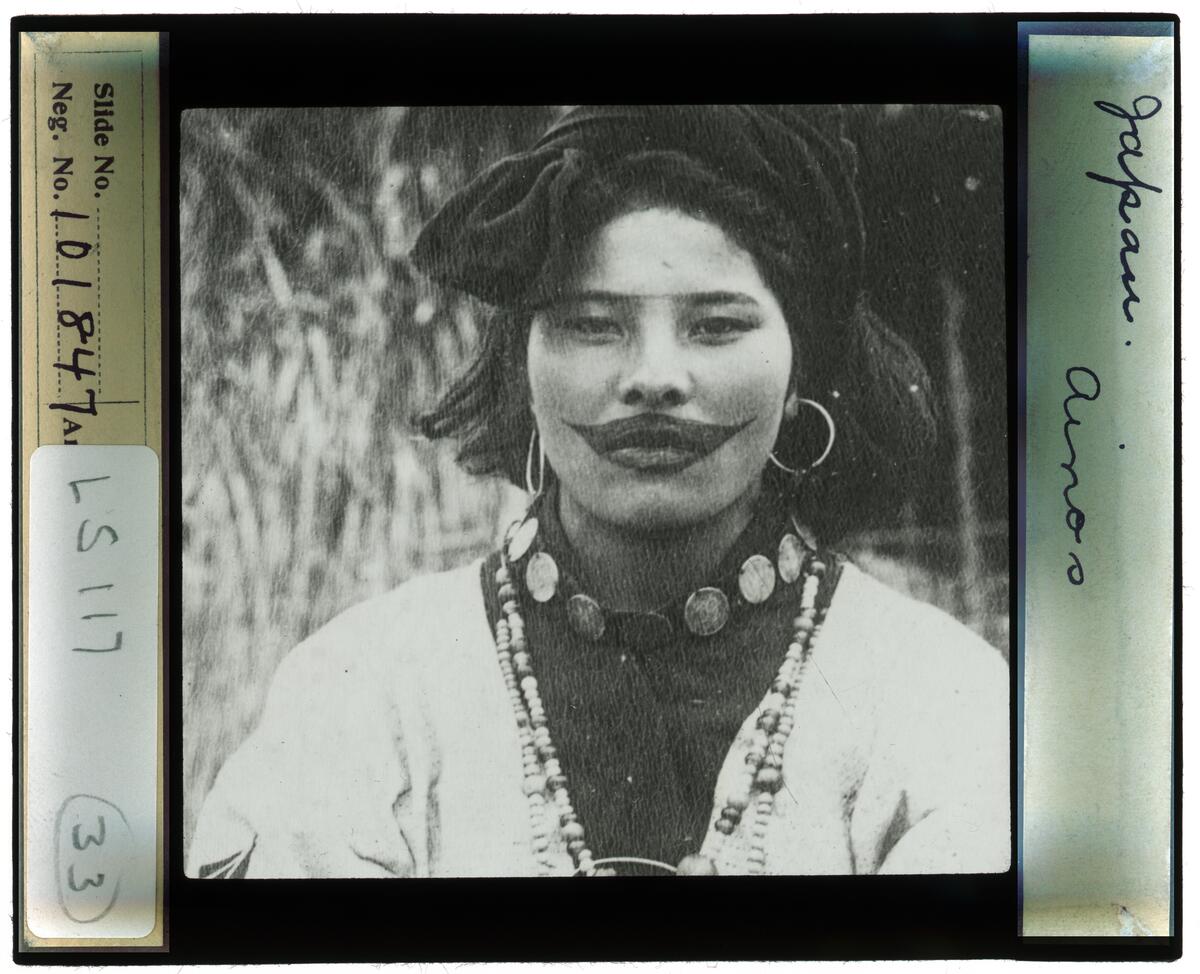

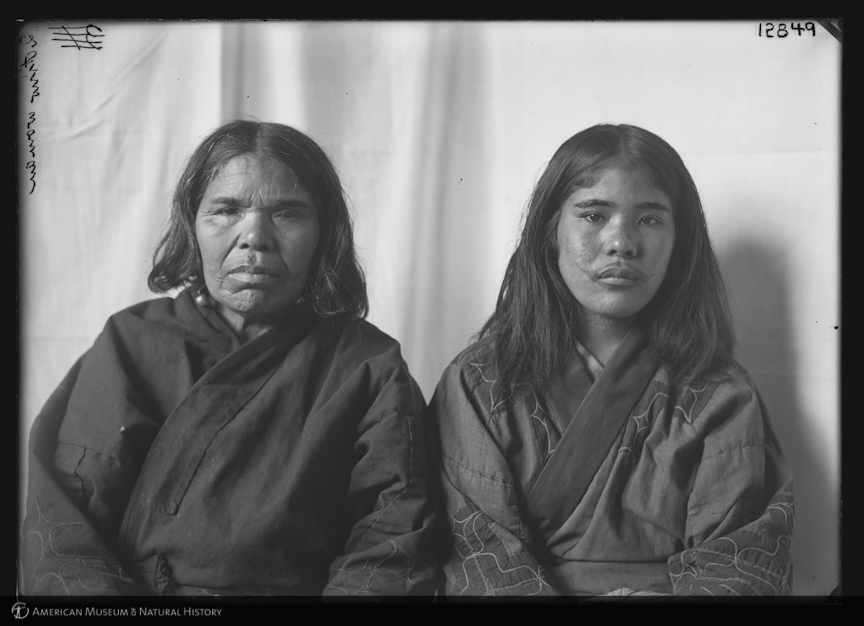

The facial tattoo represented on the female mannequin is called sinuye, or panai in some regions, and is part of Ainu ancestral tradition. Ainu women would get sinuye on their fingers, hands, arms and faces, typically beginning at age six or seven. Created by making small cuts in the skin and applying soot from a birch tree, the sinuye were completed when a woman reached adulthood. The significance of the tradition remains debated, but sinuye have been described as an important component of Ainu women’s beauty, a means of preparing the body for the afterlife and even a form of protection. In 1871, the Japanese government banned the traditional sinuye. Given the stigmatization of the Ainu people by the Japanese, sinuye like the one featured on the AMNH mannequin could make women targets of discrimination. By the 1970s, when this mannequin was made, sinuye had disappeared among contemporary Ainu. Today, some Ainu women are reviving sinuye as a mark of cultural distinction.

Photos of Ainu women with sinuye, taken during an expedition to Hokkaido, AMNH

What does Ainu culture look like today?

After years of forced assimilation, oppression and discrimination, and long national and international battles by the Ainu, the Japanese government passed a bill in 2008 legally recognizing the Ainu as an Indigenous Peoples of Japan. In 2020, just over a decade later, Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park opened in Hokkaido with the mission of “promoting Ainu culture” and serving as a base for “larger initiatives to revitalize and expand the Ainu culture.”

In addition to language, religion and dance, crafts such as wood-working and embroidery are important aspects of Ainu culture. Traditional Ainu coats, like the ones worn by the mannequins, are made of either Attush, fibers taken from the inner bark of the elm tree, or Retarpe, white fibers made from nettles. Traditionally, Ainu men collected the raw materials, while Ainu women would weave, sew and decorate the clothing. The designs were passed from mother to daughter, but each coat is unique. The robe pictured below is a fine example of a modern coat, with non-traditional, commercial cottons being skillfully combined into striking traditional patterns.

Ainu robe from the AMNH’s collection. Catalog # 70/3955. Division of Anthroplogy, AMNH

See how a contemporary seamstress reproduces beautiful Ainu embroidery work.

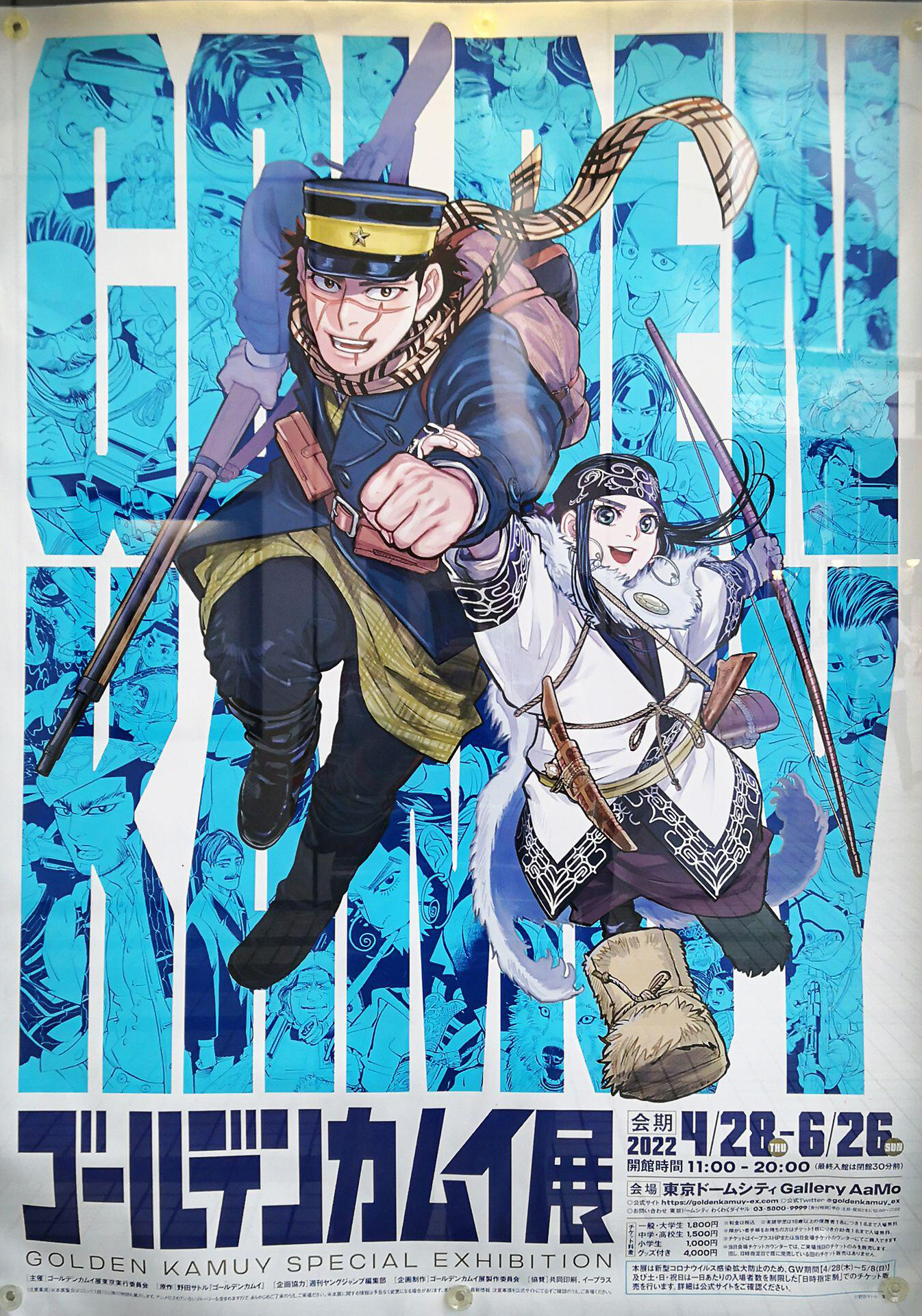

Ainu representation in Japanese pop culture

Although Upopoy, the Ainu museum in Hokkaido, explains that the understanding of Ainu history and culture is limited in Japan, and that raising public awareness continues to be a challenging endeavor, the popular Anime series, “Golden Kamuy”’ (ゴールデンカムイ) provides one example of how contemporary Ainu culture has gained greater recognition. Set in early 20th-century Hokkaido, “Golden Kamuy” narrates a battle for survival between a diverse group of men who are looking for legendary gold but with an Ainu girl, Aspira, as the hero. The show is unique in the attention it pays to various aspects of Ainu life in the 20th-century, including hunting methods, cooking and rituals.

Want to learn more about Ainu culture? Here are some resources:

Ainu Association of Hokkaido

The Foundation for Ainu Culture

National Ainu Museum