Semai: The Naked Truth

Semai Diorama in the AMNH’s Hall of Asian Peoples, AMNH

Who are the Semai?

The Semai live in the central highlands of the Malay peninsula and have maintained a common history, worldview and language despite their minority status in the Malaysian State. The display emphasizes the belief that they are a nonviolent people. This characterization was made by Robert Knox Dentan, an anthropologist who studied the Semai in the 1960s, though he offered a more nuanced view after subsequent fieldwork.

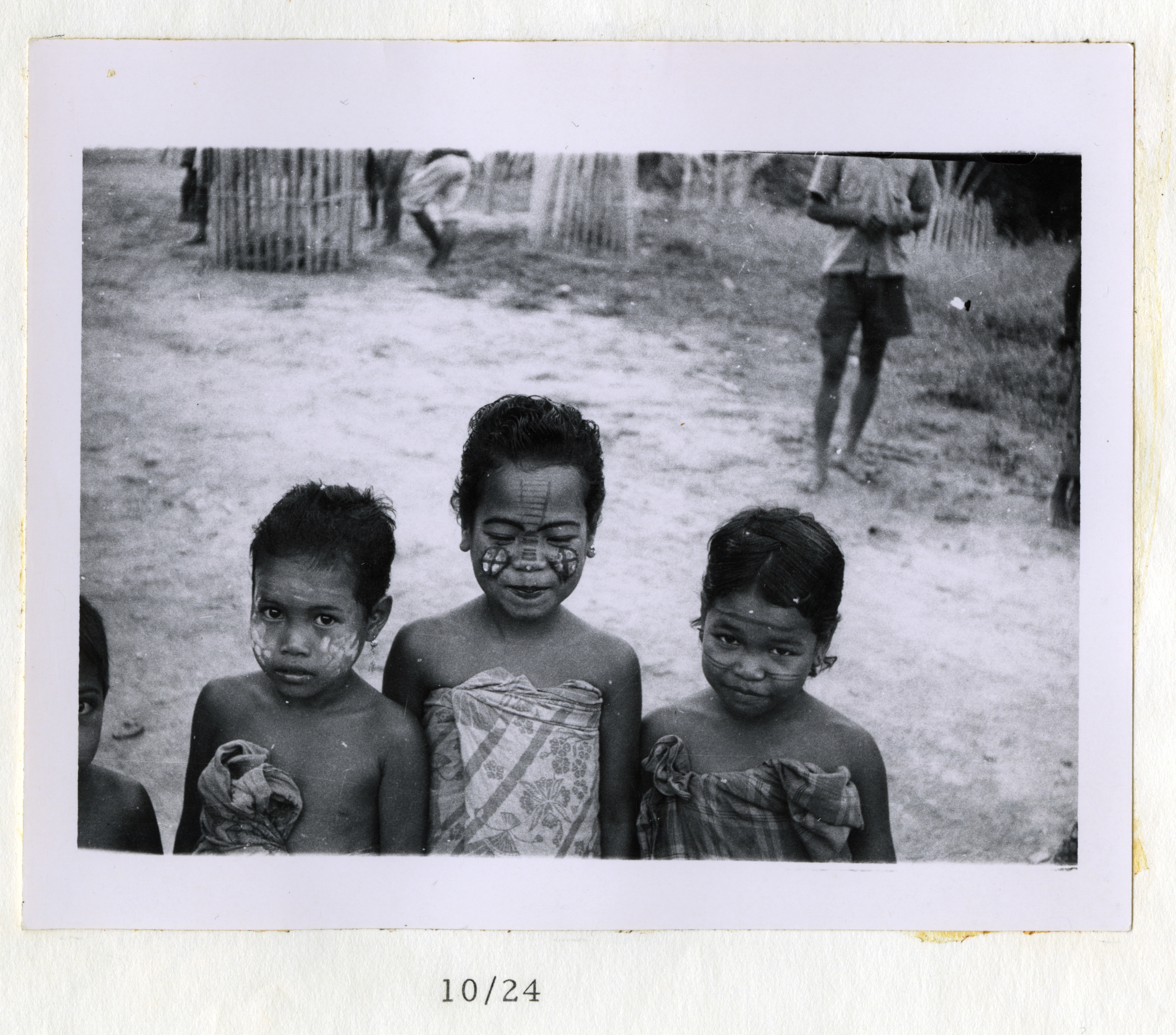

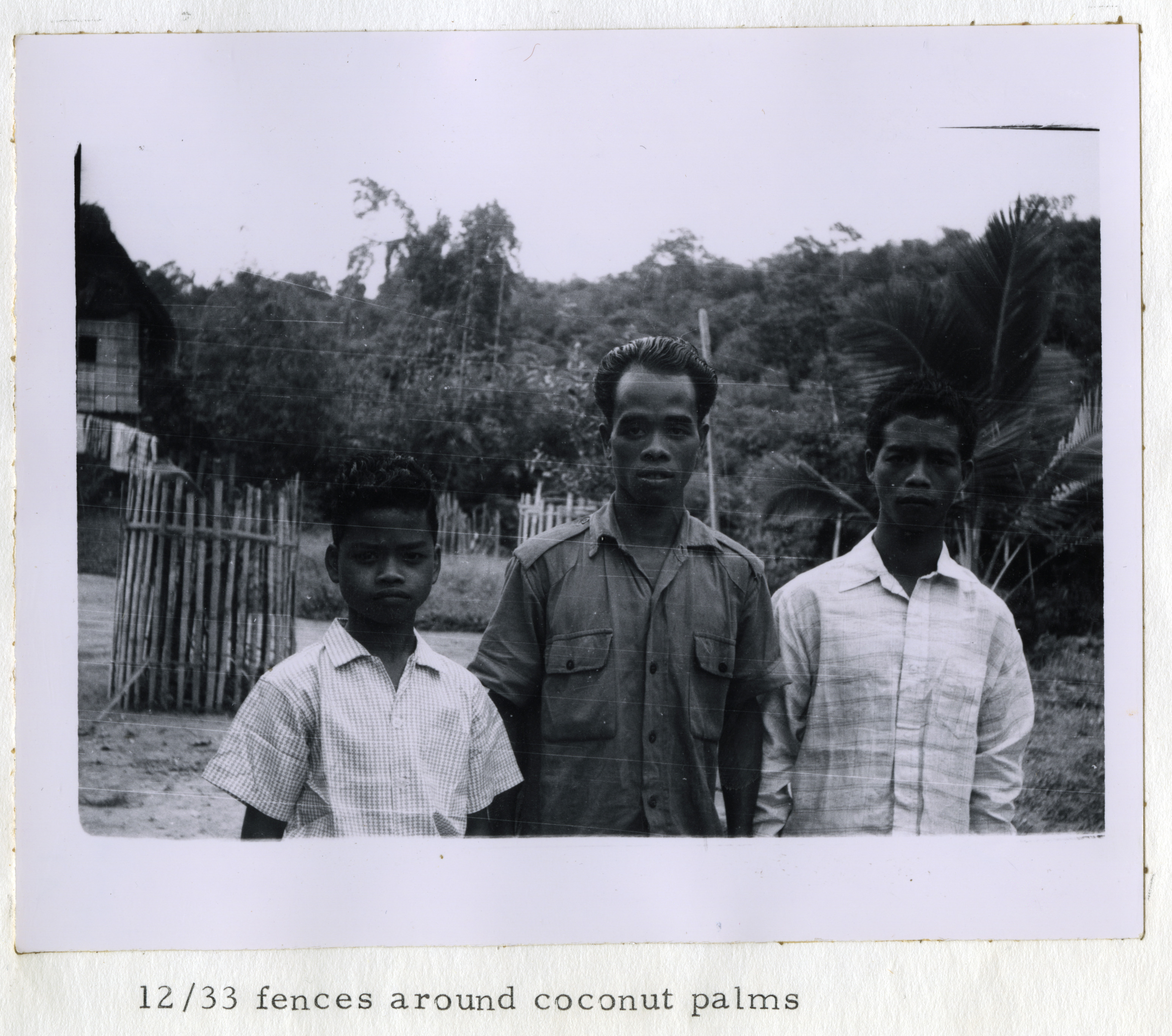

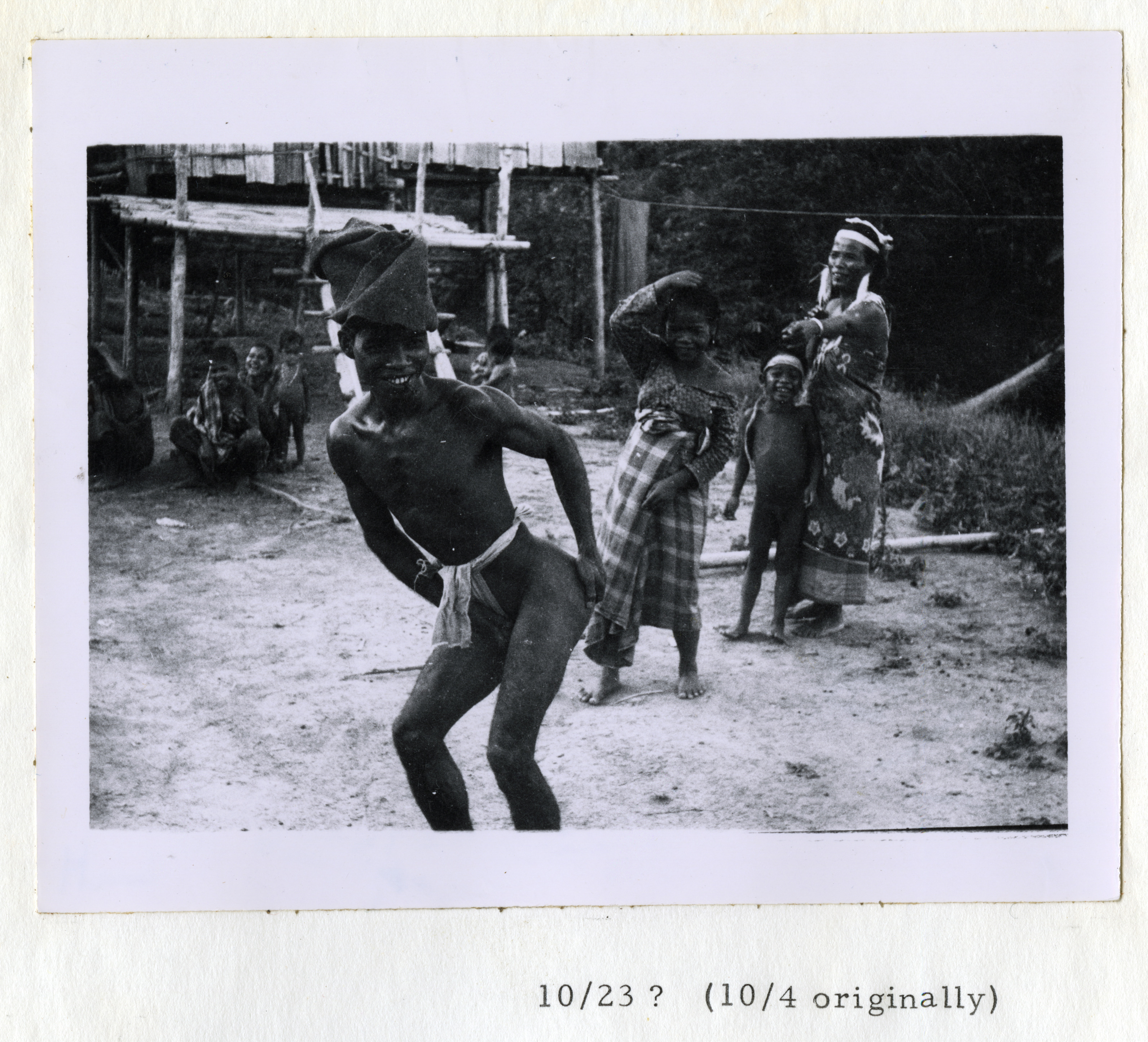

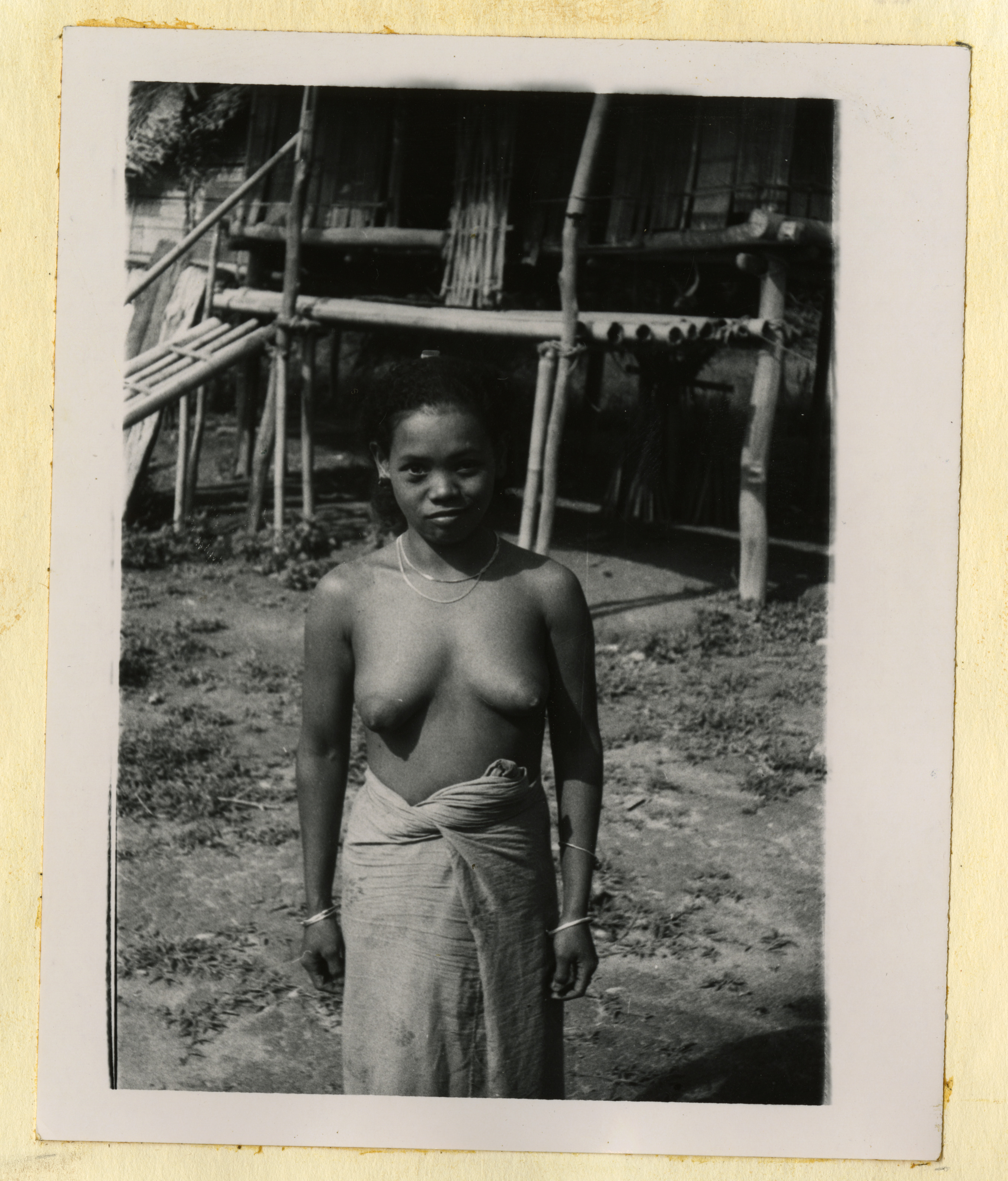

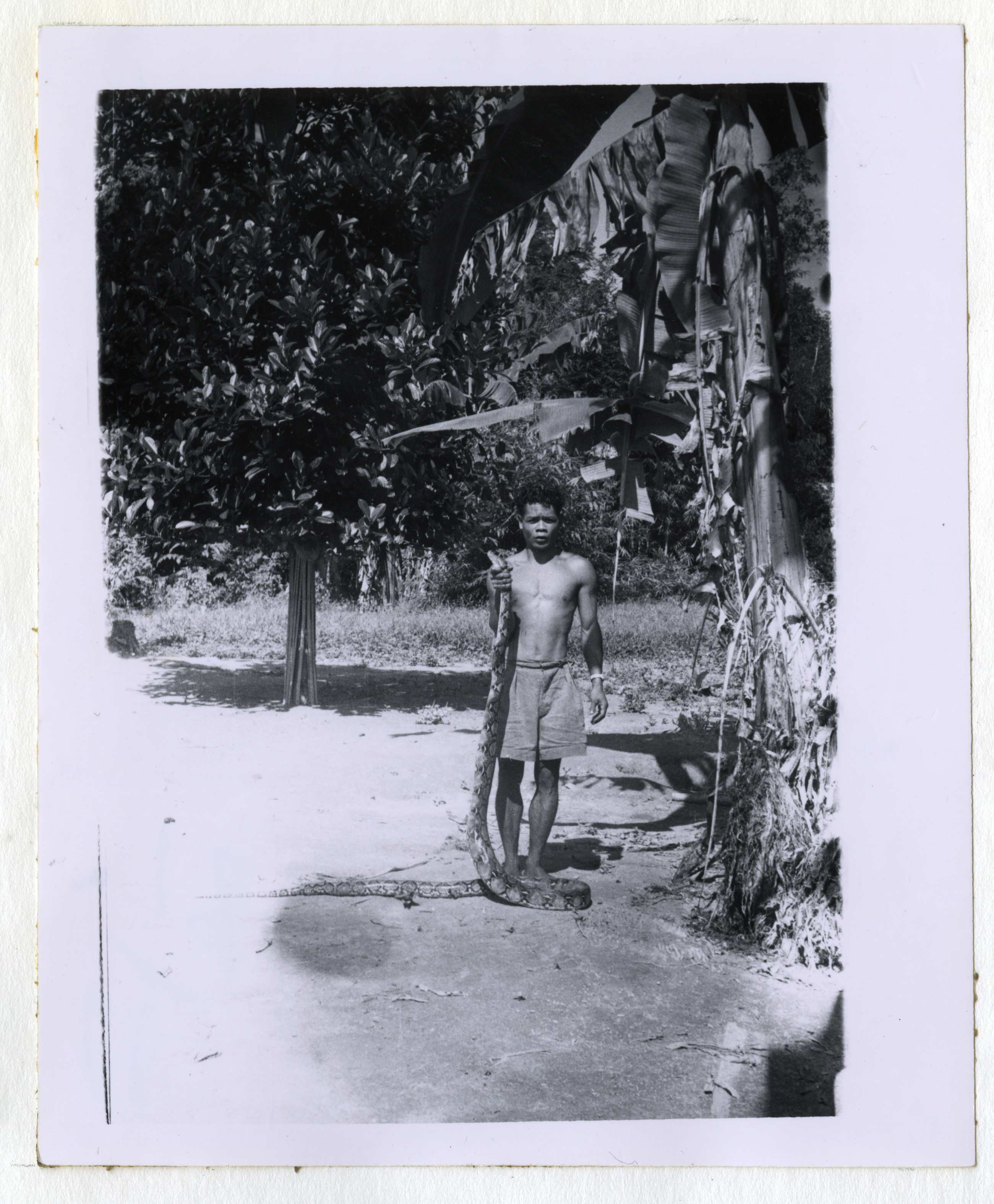

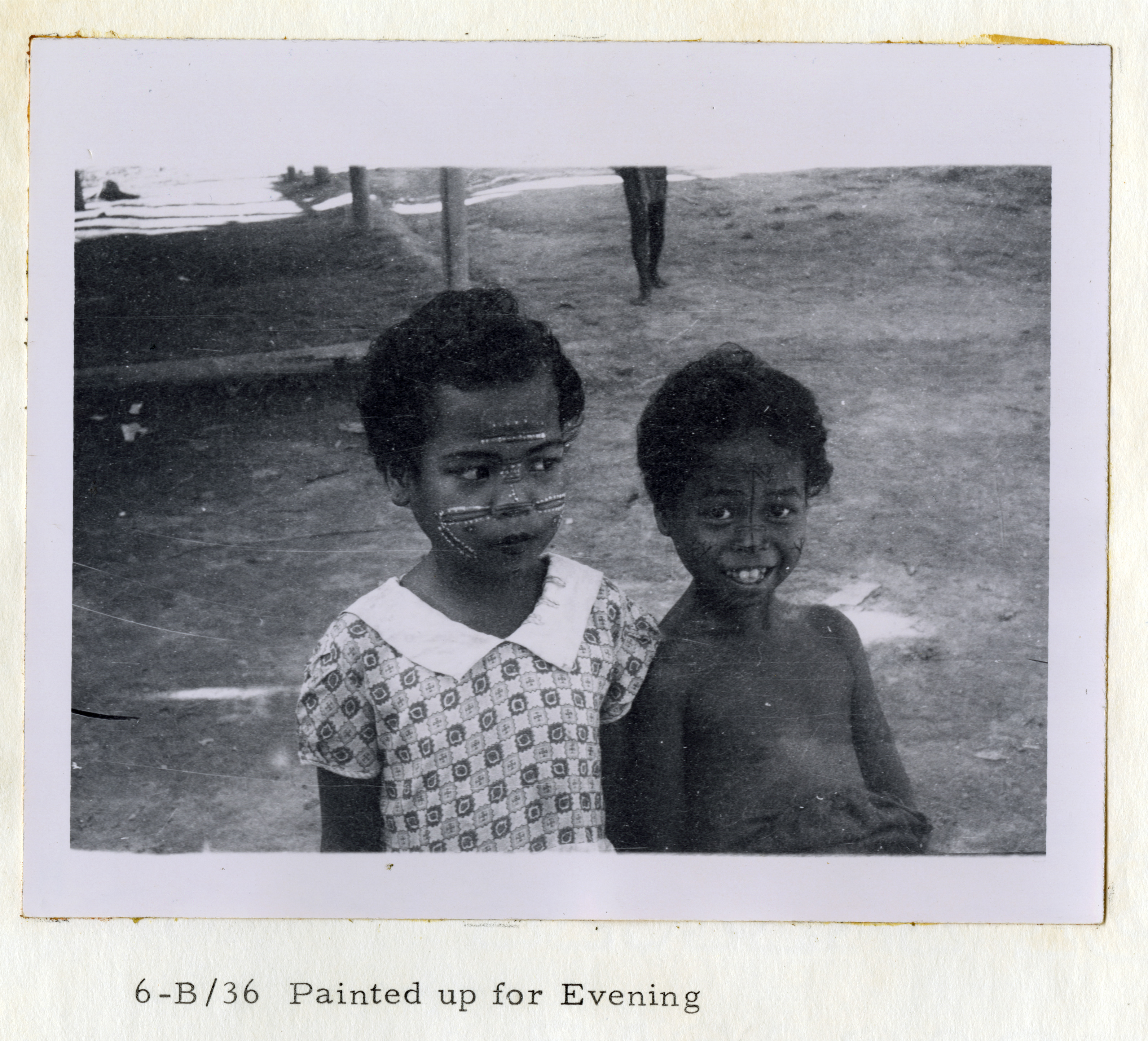

See photos of the Semai taken by Dentan during his 1960s fieldwork

How was the Semai Case made?

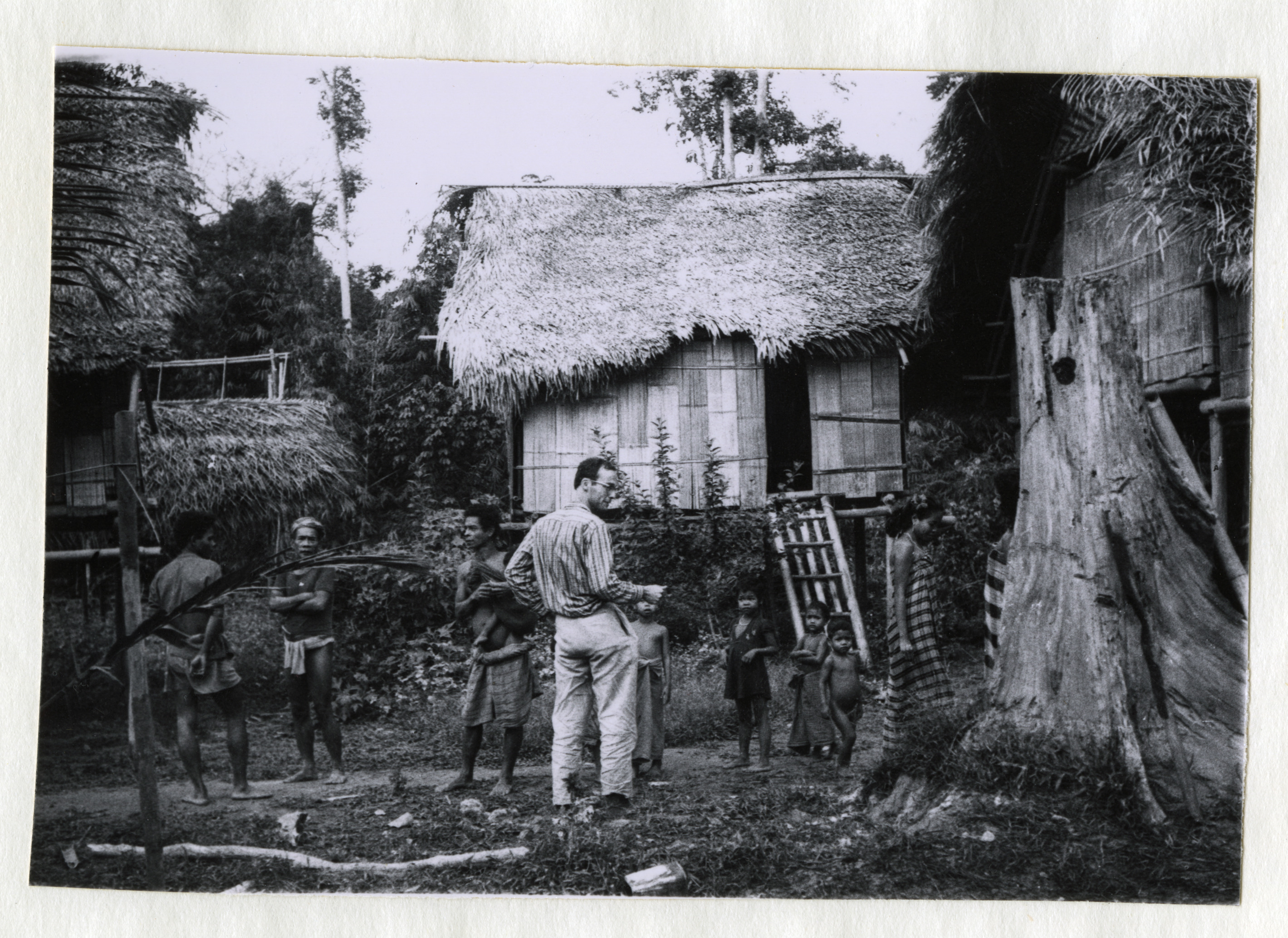

Robert Knox Dentan conducting fieldwork with the Semai in 1960s, AMNH

Dentan was commissioned to collect material for the Museum during his fieldwork studying the Semai in the early 1960s. When the Hall of Asian Peoples was created in the late 1970s, the Semai case was designed around the objects, photographs, and notes he brought back. Dentan was especially concerned that his work should be “a cooperative rather than an exploitative venture.” Several Semai had given him objects with the explicit notion that the materials would be exhibited to an American audience. Dentan hoped to honor the wishes of the Semai regarding how they wanted to be represented, as well as acknowledge the donors and their intention on the exhibition label.

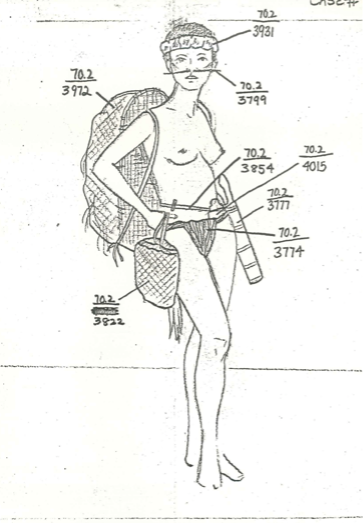

Curators and staff designed the Semai case using the materials Dentan collected. Exhibition staff created models of fish and bamboo to fill the Semai baskets, and artist Frank Mullins painted the abstract background mural. The mannequins were made by Museum sculptor Eliot Goldfinger, who created at least 16 of the 34 mannequins on display in the Hall, including the Semai and Ainu mannequins.

What influences inspired these mannequins?

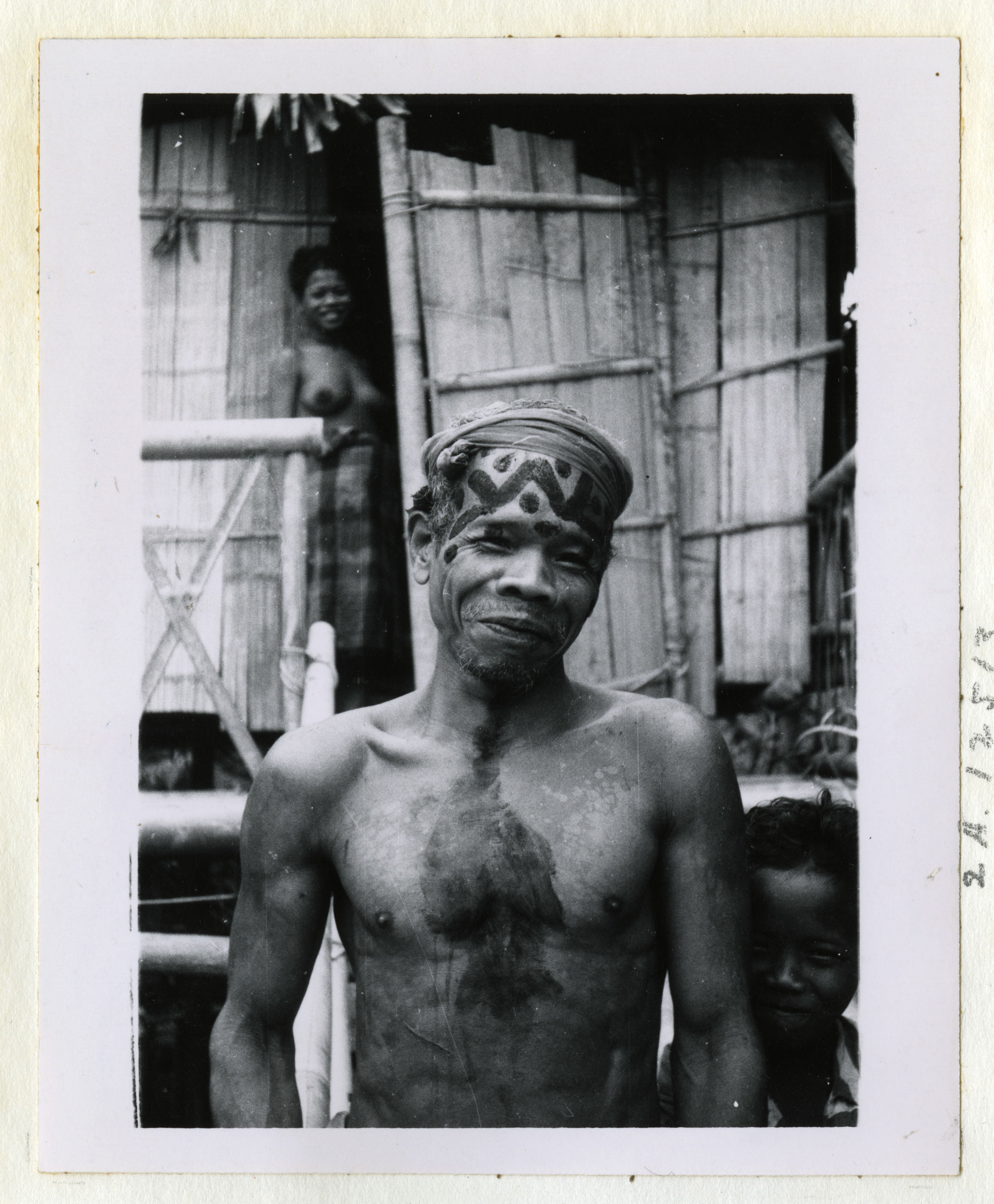

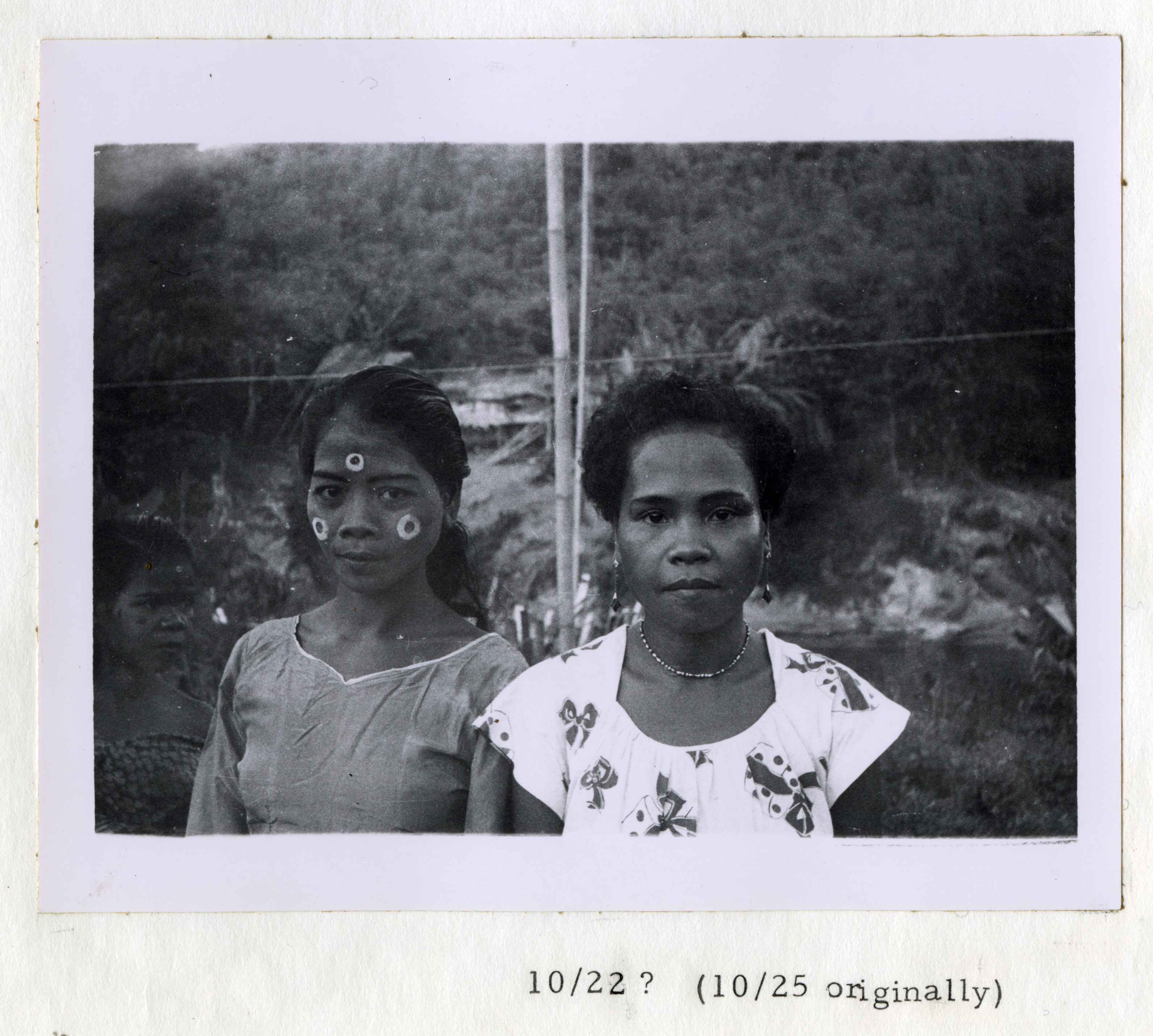

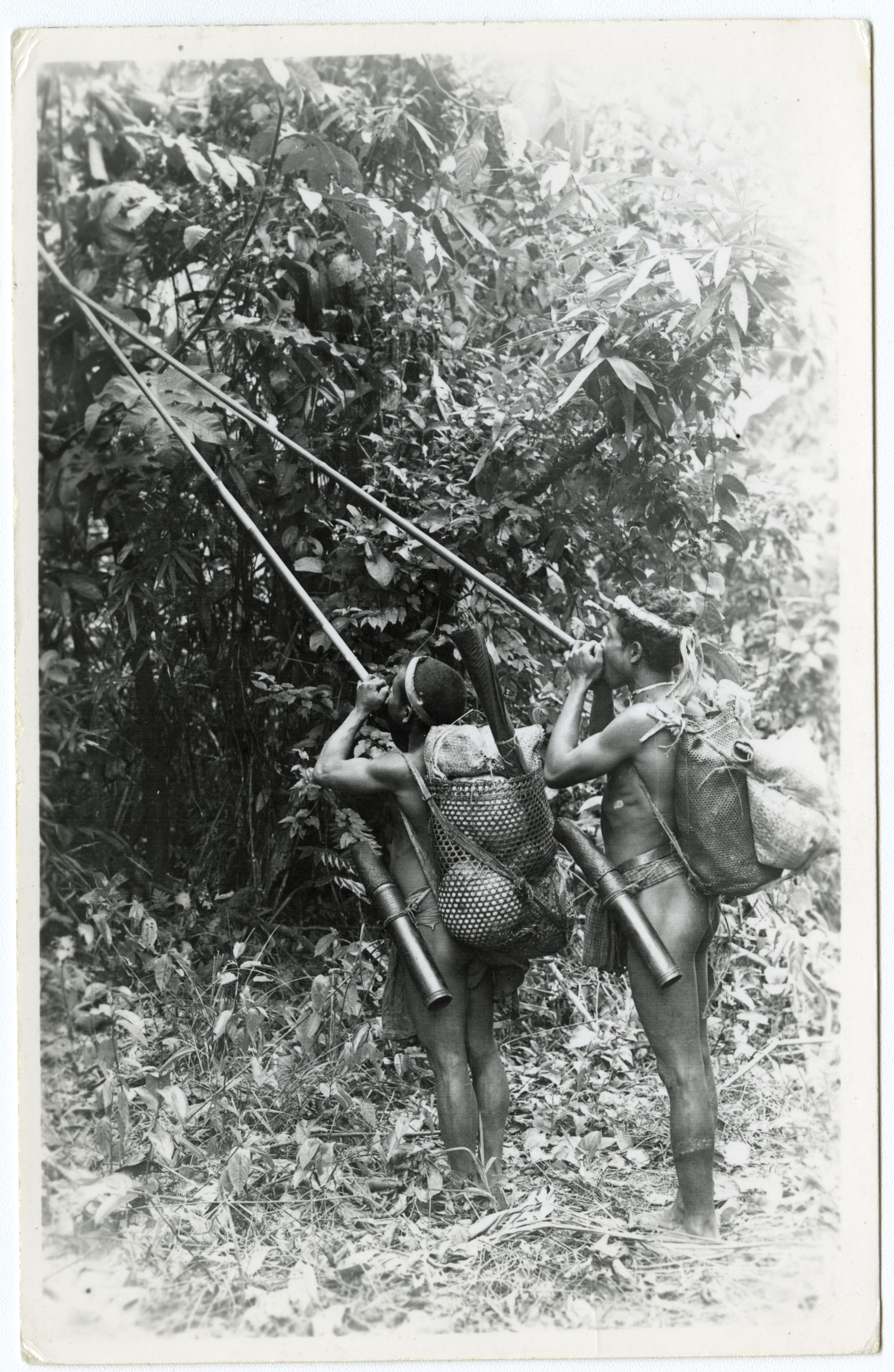

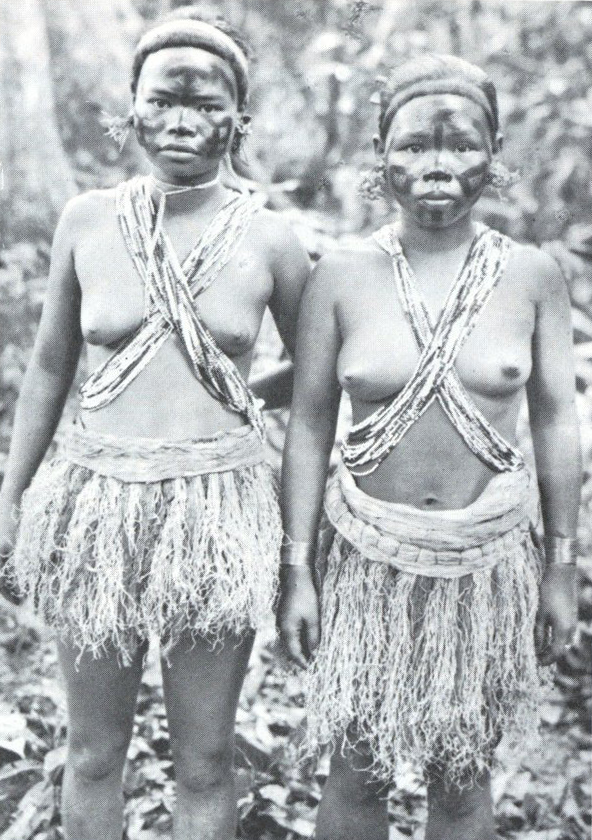

To develop the mannequins, Goldfinger first looked to Louis Carrard’s 1930s photographs of the Semai people that were featured in Dentan’s 1968 book. Goldfinger based the mannequins’ faces on Carrard’s portraits—though there are notable difference between the faces he sculpted and the photographs on which they are based.

Louis Carrard’s 1930s Photo of Semai Woman (L) and Goldfinger’s Semai Mannequin (R), AMNH

Image comparisons between Louis Carrard’s 1930s photograph of Semai men (L) and the AMNH Semai display case (R), AMNH

Image comparisons between Louis Carrard’s 1930s photographs of Semai women (L) and the AMNH Semai display case (R), AMNH, Courtesy of Eliot Goldfinger

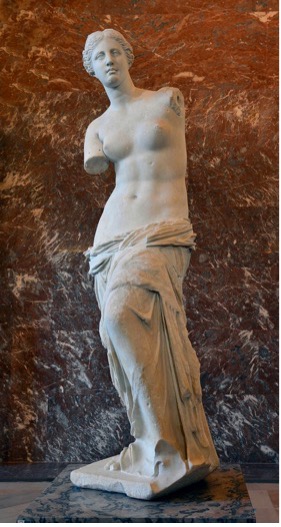

Mannequin Sketch (L), Unpainted Mannequin (M) and Venus de Milo in contrapposto pose (R)

Division of Anthropology, AMNH

Courtesy of Eliot Goldfinger

Goldfinger used the photos shown above as references for the Semai mannequins. He relied heavily on Carrard’s photograph for the male figure, replicating the pose as faithfully as possible. In contrast, the female figure’s posture is very different from the women in the photos. While they stand upright, with their weight evenly distributed on both legs, the mannequin is in contrapposto, carrying her weight on one straight leg while the other is relaxed and slightly bent. This dynamic pose is common in Western sculpture, as exemplified by Venus de Milo. Following fine art tradition, Goldfinger hired a dancer from the Upper West Side of New York as a model for the mannequin—she was the appropriate height, but he adjusted her body type to fit that of a Semai woman. The female figure that you see in the Hall today is a combination of these many inspirations.

References

Dentan, Robert Knox. (1992) The Semai: A Nonviolent People of Malaya. Harcourt Brace College Publishers.

Eliot Goldfinger Interview (2023) [Video Transcript]. AMNH.

3 February 1978, Letter from Dentan to Wilder, HOAP Papers