Korea: A Governmental Intervention

An Official Dialogue

In 1984, AMNH and the Korean Cultural Service (KCS) — part of the Korean Ministry of Culture – collaborated to redesign the Korean diorama.

The original Korea diorama, installed in 1980.

AMNH

Why was the diorama redesigned?

From the opening of the Hall of Asian Peoples in 1980, the Museum received complaints from visitors of Korean descent about its inaccurate representation of Korean culture. KCS offered to help the Museum create a new exhibit. Among other efforts, KSC commissioned a Korean designer, Young-Kyu Park, to work with the museum.

Click below to read correspondence from the AMNH Archive.

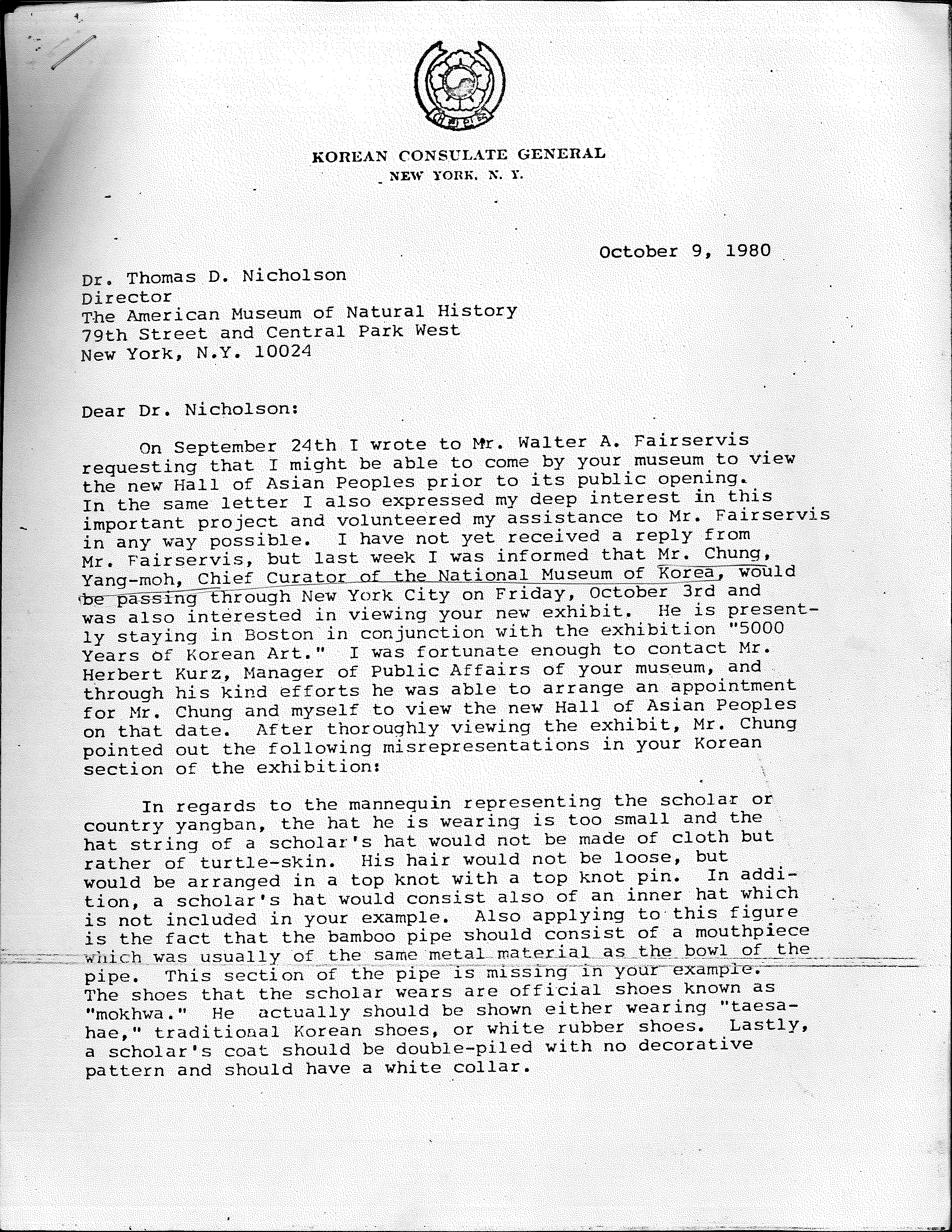

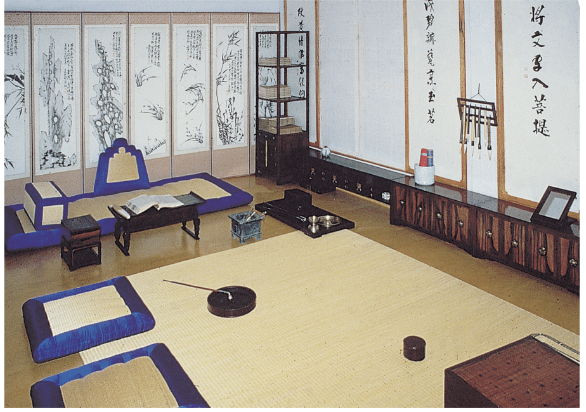

The redesigned diorama.

AMNH

What does the diorama represent?

The diorama depicts a scholar’s studio and a woman’s inner room in an eighteenth century upper-class Korean home. A scholar sits in his studio reading a philosophy text while his wife manages household affairs from the privacy of her own space.

AMNH

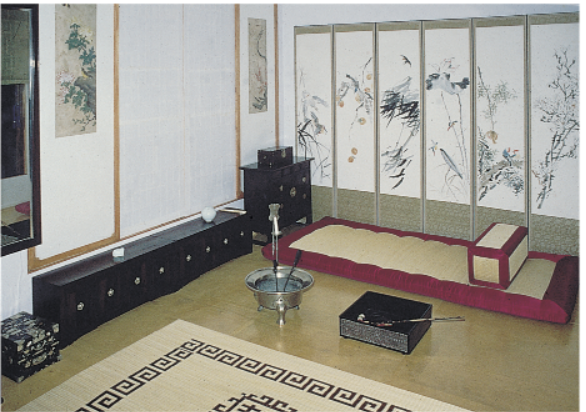

Why is the diorama divided into two rooms?

The designer chose to depict both a scholar’s studio and a woman’s inner room as he believed the gendered rooms were distinctive features of a traditional Korean lifestyle. However, the limited space available constrained the design and he used mannequins to catch the viewer’s eye.

How would the furniture be placed if the designer had adequate space to show a full scholar’s studio and inner rooms?

Unofficial Dialogues

Meet some of the people who contributed to the redesigned diorama.

Courtesy of Young-Kyu Park, 2022

Diorama Designer: Young-Kyu Park

An expert on traditional Korean furniture, Park was an art student at Pratt Institute when KCS commissioned him to re-design the case.

Courtesy of Laurel Kendall, 1984

Model for the Wife Mannequin: Chong Hwa Lim

Chong Hwa Lim worked as an administrative assistant at the Korean Traders Association when Park asked her to model. He thought her round face exemplified traditional Korean beauty.

Courtesy of Laurel Kendall, 1984

Model for the Husband Mannequin: Jung-Ho Kwon

Park asked Kwon, an art student at Pratt Institute who had taught at Daegu University in Korea, to model because Park believed Kwon had the look of a country scholar.

Excerpt of the interview with Young-kyu Park

The Korean diorama in AMNH’s Gardner D. Stout Hall of Asian Peoples is one of many exhibits on Korean culture designed by Young-kyu Park. An expert on traditional Korean furniture, Park worked at the National Museum of Korea before he came to New York to study at the Pratt Institute in 1982. While living in New York in the early 1980s, Park also worked for the Korean Cultural Service’s Gallery Korea. Now a retired professor, he is writing a second book about Korean furniture.

Dr. Laurel Kendall is Curator of Asian Ethnology at AMNH and an anthropologist who writes about Korea. She collaborated with Park to redesign the Korean diorama.

K=Laurel Kendall

P=Young-kyu Park

K: What did you think about the old Korea diorama at AMNH?

P: The contents were distracting, displayed in a limited space. They did not communicate anything meaningful to the audience. The colorful backdrop had nothing to do with Korea and the objects on display did not stand out against the garish colors. The mannequins didn’t look like they belonged together. The man was standing in everyday dress, smoking, while the woman sat next to him in a wedding dress. The man should have had the look of a scholar, an intellectual, but his face was blank. The female mannequin, though, in the manner of Korean women, conveyed a softness of expression with a suggestion of her true inner strength.

K: How did you decide on the changes you made to the new display?

P: I would have wanted to show a full sarangbang (scholar’s studio) and a women’s inner room but because of the space constraints, I thought it would be better to use mannequins than to just exhibit small household objects. […] The sarangbang, with its calm and quiet atmosphere, was a place for scholarly study and contemplation. It shows the most refined aspects of Korean life, and this is what I wanted most to convey.

K: There was a man and a woman chosen for the mannequin’s faces. What sort of man and woman were you looking for?

P: I wanted the man’s face to suggest intelligence and a strong will, like an old-fashioned scholar-official. The woman should have the round face of an East Asian woman, a full face, the face of a kind and gentle person is also fierce on behalf of her family and household.

[…] Before I got married, my grandmother remarked about a woman on the TV screen, “Her face: it’s round and pretty. I hope that our youngest grandson gets such a bride.” The thought stayed with me.K: If you were able to design the case again, what would you do?

P: If there were more space, I would have wanted to include some really fine traditional furniture and accessories to give a more refined sense of the scholar’s studio. I might also include something about Buddhist culture and the mudang (shaman), the Korean lifecycle and the variety in Korean culture.

But if we are talking about the current space, I would want to change the male mannequin’s face for something smaller and thinner, the face of an intellectual. Once the cast was taken, the mannequin looked stubborn, like a greedy person, not like a scholar. So, I thought that I had made some mistake.

Excerpt of the interview with Eugene Hannah Park

Eugene Hannah Park’s aunt modeled for the female Korean mannequin in 1984. Park is a curator in contemporary art from Seoul, Korea. Curious about the methodologies that intersect different times and spaces, she curates platforms exploring the possibility of learning from various mediums. She is currently working on a documentary about “visiting” her aunt in the American Museum of Natural History, a story which entangles personal history, family belonging and national and cultural identities

Park was interviewed by Dr. Laurel Kendall, Curator of Asian Ethnology at AMNH, and Qingquan Ma, Sophia Sze Nga So and Gennie Xiaojing Zhang, students in the Columbia University and AMNH MA program in Museum Studies.

Interviewers – I

Eugene Hannah Park – E

I: Do you remember when you first saw the mannequin modeled from your aunt’s face? Do you remember how you felt at the time? And have your feelings changed over time?

E: When I was 9 or 10, my mother took me to AMNH. I was looking at the Korean diorama when she said, “Hey, that’s your aunt.” I was trying to process that, and she then told me that the mannequin in the diorama has my aunt’s face in plaster. Looking carefully, I found a resemblance.

It was shocking because my aunt was very close to me, and her face was something I looked at every day. It’s someone that you love, and are very close to, so much so that you eat, sleep and play together.

I never expected anything friendly to pop up in the museum, beyond the glass wall,

because to me then, museums were places of “exotic” things and people you don’t meet in daily life, like dinosaurs’ stones, magical objects… places full of mysteries and surprises.

I visited New York and the diorama again when I was 20. It wasn’t shocking anymore, but something was different. My aunt is a grandmother now and she ages. I could see the time flying and her face changing, although the mannequin’s face stays the same. There were two identical faces but the layers of time made a difference.

I: Why did your aunt decide to volunteer for face-casting when she was asked? Has she shared any memories about the experience of the face-casting session?

E: My aunt was spotted in the elevator by an employee of the Korean Cultural Service who suggested that she should be the model of the mannequin. My aunt shared the suggestion with our family. My grandmother and my mom said, “yes, she looks like a North Korean woman.” (At the time, there was a popular perception that beautiful women come from the North and handsome men come from the South). Her husband supported her because it was not a photograph, it was a plaster cast on her face, not the whole body, and my aunt said to him, “Oh, I think it might be a very exciting experience.”

[…] she remembered going inside the casting room and using the back door of the museum. She first sat down in the chair, and people started to put white stuff on her face. She was scared because the plaster covered her eyes, and she thought she might not be able to breathe when it was all on her face. I think she got paid around $30 to $50 for her volunteering.I: How does your aunt feel when she visits AMNH and sees her younger face on the mannequin nowadays? Does she introduce her companions to “her” mannequin?

E: I asked her several times how she feels about looking at herself as a mannequin and she now thinks it might be a fun story to tell her grandchildren, because her grandchildren might visit the museum and see, “that’s my grandmother!”

A few years back, she visited the museum on a snowy day with her friend. Usually, she felt shy. But that time, because she was there with her friend alone, she made a pose next to the mannequin and she thought it was just interesting. Her recent response was, “Oh, now I’m old, nobody cares about my face, so I can tell you my stories.”

![] Exterior view of a traditional household in Korea shows the scholar’s studio on the left and the inner room on the right behind the wall. Courtesy of Young-Kyu Park, 2022](https://archaeology.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/25/2022/04/Exterior-view1NEW.jpeg)