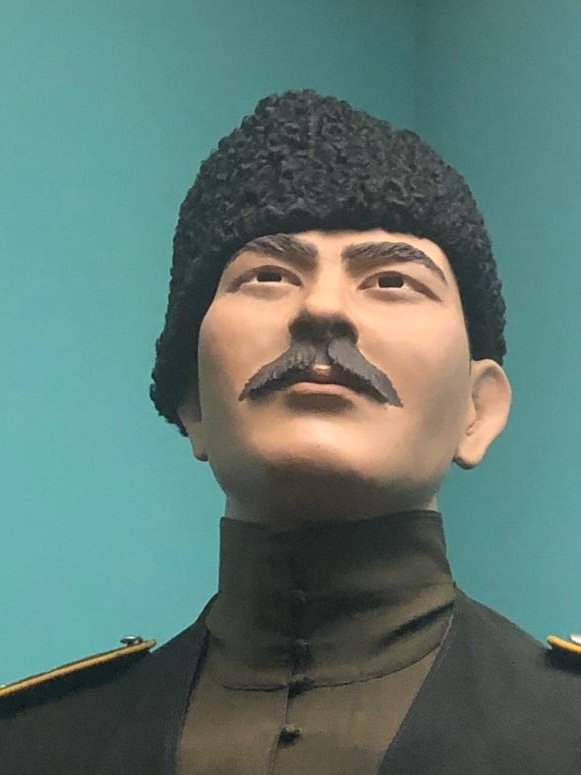

COSSACK MANNEQUIN

Ethnographic museums rarely tell the stories of imperial pasts. As an exception, one of the cases in the Museum’s Hall of Asian Peoples represents the Cossack people—a military class best known for aiding the Russian Empire’s expansion. While some museum mannequins are anonymous and have minimal features, the figure in this case was modeled after a known historical figure named Constantine Agoeff, whose biography is included in the Museum’s extensive archives. The case also holds objects from around Constantine’s lifetime, including a map that illustrates the land that Cossacks occupied during Russia’s expansion.

Cossacks in the Russian Empire

In the 1500s, Russia began expanding its eastern empire, chasing the immense wealth generated from the fur trade in Siberia and the Russian Far East. Russian hunters and traders sought access to the valuable fur of the sable, a small forest-dwelling animal, to sell to the European markets in the west. To meet this demand for fur, Indigenous communities were forced to pay the yasak, an obligatory tribute of fur made to the Tsar. By the 1600s, the fur trade had become crucial to the Russian economy, comprising 10 percent of the Empire’s total revenue.

The Cossacks were an essential component of Russia’s colonization of Siberia; they conquered local communities who were subsequently forced by missionaries to accept Orthodox Christianity, Russia’s state religion. Under Cossack rule, Indigenous beliefs and customs were brutally suppressed through acts of extreme violence. Groups such as the Sakha (Yakut) were among those brutalized, robbed, forced to convert and killed by the Cossacks. Despite their fear of reprisal if they were discovered, many Indigenous people continued to secretly engage in shamanic practices throughout this period. Learn more about Sakha people and their place at the AMNH here .

Russian Expansion Map

This work by Russian painter Vasily Surikov depicts Yermak Timofeyevich, a Cossack soldier who is revered as a hero in Russian folklore, conquering Indigenous, non-Christian Siberian communities. Notice the religious iconography on the banners of the Russian side.

Lasting Impressions

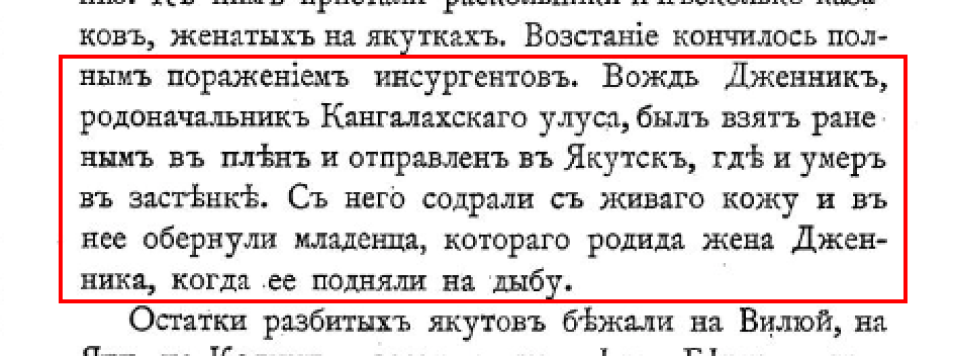

In 1895, the Anglo-Jewish journalist I. W. Shklovsky published In the Extreme North-East of Siberia, a book that includes descriptions of some of the atrocities that Cossack soldiers committed against Indigenous communities in Siberia in the past. Jennik, the man mentioned in the excerpt below, was the leader of one of the last Sakha rebellions of Indigenous people against the Russian colonizers. Shklovsky writes,

Stories such as this have lingered in the hearts and minds of Indigenous people to this day. Where institutions represent the Russian Empire and its Cossack soldiers, it is essential to tell this part of the story, and to acknowledge the pain and suffering that Indigenous communities experienced.

The Man Behind the Cossack Mannequin

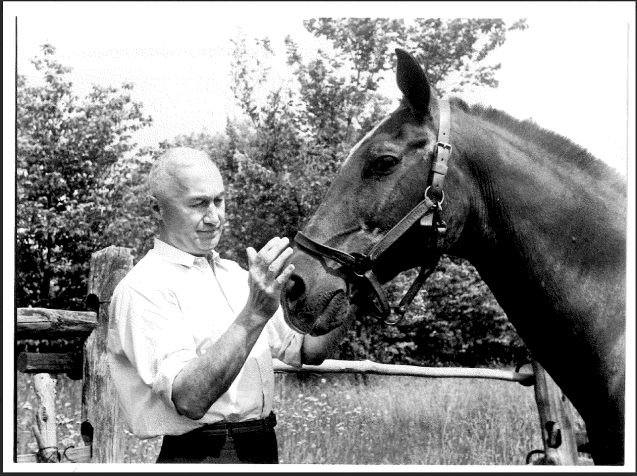

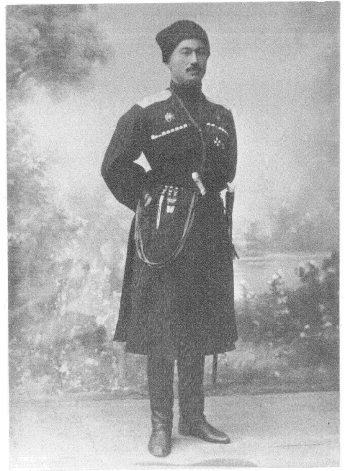

This uniform, which originally belonged to General Constantine C. Agoeff, was donated to the museum by the Cowgills, a Connecticut family who had employed Agoeff for many years and romanticized the horse-riding Cossack people.

Agoeff was a Terek Cossack from the Caucasus who achieved significant military success during the First World War, fighting first the Austrians and then the Bolsheviks. During his service, he earned the St. George’s Cross, Russia’s highest military honor, which was personally pinned to his chest by the Czar.

After the Russian Revolution and the fall of the Czar in 1917, Agoeff fled Russia for fear of persecution by the Bolshevik Army. He settled in Connecticut, not far from New York City, and secured a job at Sikorsky Aircraft. The company was founded by a fellow refugee from the Russian Revolution, Igor Sikorsky, and it served as a haven for Russian emigrants who fled Russia after the revolution. While Agoeff was working there, Major William Cowgill, who was also an employee at Sikorsky Aircraft, was in search of someone who could look after his stables. He hired Ageoff, who ultimately worked for the Cowgills for over 30 years and remained close to the family until his passing in 1971.

Lisa Whittal, a Research Assistant in charge of costumes for the Hall of Asian People’s renovation, found Agoeff’s uniform for the Museum. She was childhood friends with the Cowgills and was able to track it down through one of William Cowgill’s grandchildren. Both Lisa and the Hall’s curator, Walter Fairservis, thought that the uniform would provide for an “interesting exhibit” in the Hall of Asian Peoples, displayed under the Romanov Imperial crest in seeming glorification of the vanished Russian Empire.